Posts by mcampbelldavies

Grieving through service

The following reflection was written by World Relief Seattle intern, Katherine Abdallah. Katherine joined the team at World Relief during the pandemic, and spent her time assisting the Resettlement Team by scheduling appointments, helping tutor English, building study tools for the citizenship test, and otherwise assisting with the resettlement process under extraordinary circumstances.

“If you want to remember someone, pray to remember them, help the poor to remember them. It shouldn’t matter where she’s buried.”

It was November of 2019 and my Teta (grandmother, pronounced tay-tuh) was in the hospital. She was the strongest person I had ever known in terms of both physical strength and will. Ironically, she was incredibly petite. My mom liked to say she was about the size of a smurf, but because she had such a big personality, it was hard to remember how tiny she was.

It was even harder to see her in the hospital. A woman who used to walk wherever she needed to go and who could have easily beat me at arm wrestling (a contest I had never dared start with her), was in the hospital battling pneumonia, a hip fracture, and a stroke that had taken most of her speech, all of her mobility, and her ability to swallow.

My Teta had ten children. Seven of them lived on the west coast and sat in the hospital room to discuss her burial. Inevitably, there was some disagreement on how to handle her final preparations, hence my ammo’s (uncle’s, pronounced ah-mo) statement that it shouldn’t matter where she’s buried. We were sitting in the hospital lobby taking a break from the tension of the hospital room when he reflected on the best ways to honor the dead. As soon as he finished his sentence, I knew that I needed to do something to honor Teta after she passed.

Five months later, after fighting her hardest and giving us lots of sweet hugs, Teta went on to the place where she can finally get the rest she deserves. I miss her every day, and I try to honor her with every major decision I make.

One of these major decisions was applying for an internship at World Relief Seattle. Between her death and the time that I applied, I had given a lot of thought to how I would help other people in her honor like my ammo suggested. I wanted to help other people who had been through hardships similar to my Teta’s hardships. She was a Palestinian refugee; she was about ten years old when the United Nations recognized Israel as a nation and violence erupted between Israel and the neighboring Arab nations. Teta had to abandon her home in Gaza and run with her children to relative safety in the Jordanian city of Zarqa. When they moved to Jordan, Jordan offered no path to citizenship for refugees from Gaza Strip, so my family was deprived of legal documents, legal protections and many employment opportunities. This was in addition to the violence of the Arab-Israeli conflict and all of the routine discrimination like government checkpoints for Palestinian citizens.

After scrolling through list after list of nonprofit organizations, I found World Relief Seattle and immediately applied for the refugee resettlement internship. I felt entirely certain that World Relief was where I was supposed to be, and throughout the internship I could feel Teta approving of my decision from heaven.

My first assignment for the internship was from the ESL team with a short list of students who wanted tutoring. On my list was an elderly, Arabic-speaking woman. Before even calling her, I felt certain that we were made for each other. It just seemed too perfect that I had lost my elderly, Arabic-speaking grandmother and I was getting matched with an elderly, Arabic-speaking student. She and I bonded quickly-during our first tutoring session after I greeted her in Arabic, she said “I like you!” After a couple of weeks, she would end tutoring sessions by telling me that she hoped God gave me every good thing and she would smile at me like Teta used to. It was like Teta was offering affirmation that I was honoring her exactly how she would have wanted me to honor her.

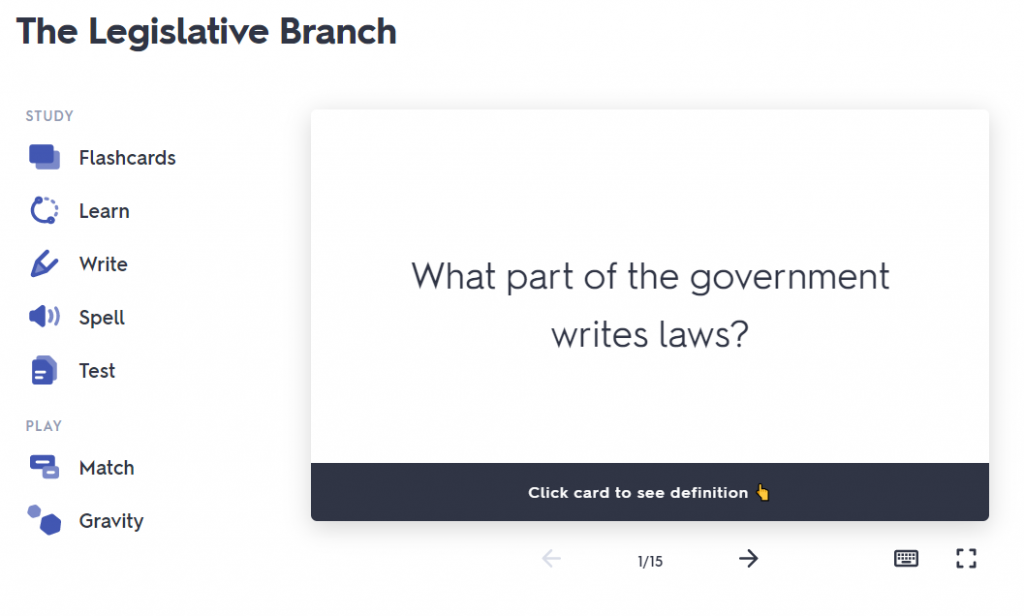

My elderly, Arabic-speaking ESL match told me that she was studying for the citizenship test and she would read parts of her study materials to me during our English practice. This inspired my internship project: creating ESL-friendly Quizlet sets of flashcards for the entire citizenship test, which provided audio, visual, and written tools for studying the test from a computer, laptop, or print.

After I was about 60% done with my project, USCIS announced a new version of the test to take effect one week before my project was scheduled to be completed. The new test replaced the 100 questions with 128 questions and required 12 correct responses instead of 6. The wording of the new test condensed more information into each question, to the point that it was faster and easier to start over than try to edit my old work. I became filled with a sense of urgency to finish a quality project. Any form of the citizenship test is challenging, but knowing that my ESL match had been studying so hard and would now need to learn so much more broke my heart. In the midst of the frustrations at starting a new project, it was rewarding to complete a timely internship project.

Timely is a funny word for the times we’re living in. With the pandemic, presidential election, and every other challenge from this past year, it often feels like nothing is timely, anymore. I can say with certainty that the resettlement internship was timely for me in my phase of grieving. World Relief gave me several special gifts. I was given a platform to explore my family’s heritage as refugees while helping other refugees, opportunities to study the US immigration system, a renewed sense of purpose and passion for helping people, and a large measure of healing. Teta died during the pandemic, shortly after quarantine started, so saying goodbye felt disrupted and incomplete. I feel like I was able to say goodbye to her through service at World Relief.

A growing family

The following is a reflection written by Liz Hadley, Employment Specialist at World Relief Seattle.

Pulling up to the McGlashan’s house, it seems as though you’re looking at the perfect retirement set up: a lovely house set on a quiet suburban street with two massive golden retrievers bounding out the front door. Their home appears to be a place to hunker down and, with the kids all out of the house, enjoy the life phase you’ve planned for years.

But in retirement, Lisee and Doug’s family is actually growing: they welcomed two boys into their family last year, and more are being added to the family every few months.

The two young men pulling up into Doug and Lisee’s driveway seem by all accounts, typical young men: driving a nice car, sporting their favorite soccer team’s jersey, eager for the pizza to be delivered. But as they hug Doug and Lisee saying “hi mom, hi dad”…I’m suddenly aware that we’ve met a family with an incredible understanding of what ‘family’ means.

These two young men, Kwaku and Arafat, are both from Ghana. Doug and Lisee are from the US. Having met only a few months ago, they call each other by familial terms now: “these are our boys” Doug and Lisee will tell you; “for me, they are my mom and dad” Arafat explains.

This unlikely family began from a bit of humorous rejection as Doug explains. Having signed up to be a Cultural Companion with World Relief, Doug was paired with a young man who had just been granted asylum. After trying to meet up a few times and begin building a relationship, the connection fizzled out as the young man quickly became busy with work and English classes.

So Doug tried again.

This time, it seemed that the new potential match wasn’t too interested in having a cultural companion. Three times Doug put himself out there as a cultural companion to no avail, leading him to begin wondering with a smile and slight laugh if it wasn’t him that was the “issue”. But time has a way of working things out, and Doug’s persistence led him to befriend and come to love an unlikely group of young men who, far from their own families, have come to see Doug as a father and Lisee as their mother here in their new nation.

In the summer of 2017, World Relief introduced Doug to Arafat. When you meet Arafat, you meet a gentle, kind and pensive young Ghanaian who stands tall above you, offers a radiant smile and speaks in what feels like an impossibly low register. During their first meeting together, World Relief’s Cultural Companion Coordinator sat with them to help with the admitted awkwardness of meeting a stranger for the first time, but after that they were on their own! And lucky for Doug, this match stuck.

In their first few times meeting up, Arafat referred to Doug as “Sir”…but the formality didn’t suit Doug. In searching for a new way to refer to one another, Arafat asked if he could call Doug “dad”, This time, the term seemed fitting.

Conversations quickly turned to classic father/son topics: what to look for when buying a car, plans for furthering your education, understanding what’s happening on the field at an American football game, and what qualities to look for in a partner.

Arafat grew to know Lisee as well and naturally referred to her as “mom”. When I met with the family over pizza to hear their story, Arafat explains to me that he lost both his parents when he was young. He grew quiet and, in a manner fitting of a toast, described how much respect he had for Doug and Lisee, how much they had helped him, welcomed him and loved him. Turning to look at Doug and Lisee, Arafat said “I love you dad, I love you mom.” It was all I could do to not drown my slice of pizza in tears.

On the kitchen counter when you walk into the McGlashan house, sits a little shrine capturing their family: a photo of their adult daughter, a picture of their two Goldens, and a small balloon that says “I love you mom”. Lisee explains to me that this gift is from her boys. For Mother’s Day this past year, Arafat brought over flowers, a massive teddy bear, and this balloon. The balloon now sits amongst the mementos to biological children and pets they’ve cared for over years. It’s clear that the concept of family is being blown wide open for the McGlashans.

It’s not only Arafat whose been added to the family though–he has the natural ability and tendency to connect people. In being resettled by World Relief, Arafat was placed in an apartment with a handful of other young men, many of whom are now his close friends. As a bit of a leader amongst the apartment, Arafat began introducing his friends to Doug and Lisee, and over time and several shared meals, these young men also grew to trust and love the McGlashans, calling them mom and dad as well. When Doug and Lisee now talk about “their boys”, it’s this group of young men they’re referring to.

To be honest, when I first heard the “mom and dad” thing, I was a bit skeptical and wondered how deep these relationships had actually gone. Lisee shared with me a story from early on in their relationship though that reminded me of something my parents would do for me, thus dispelling my skepticism. Over the summer, Doug and Lisee took a vacation and were without cellphone coverage for a few days. During their time away though, they just had to find reception and call their boys to check in and see how everyone was doing. It turned out everyone was doing just fine, but one of the boys was anxiously waiting for them to return home so he could get their advice on a potential car purchase. After all, he had promised before they left not to make the purchase without first running it by them. It’s a subtle gesture – calling just to check in – but it communicates volumes. Arafat and his friends never expected to have this in America: someone who would call just to check in, just to say hi, just to remind them that someone cared for them and saw them. Hoping to find safety in America, they had also found family.

The other young man joining us for pizza today is Kwaku, another Ghanaian who Arafat met through World Relief, and another one of “the boys”. Kwaku

and Arafat didn’t know each other back in Ghana. Though from the same city, they had grown up in different communities; one being raised in a Muslim community, the other in a Christian community. Today before sitting down to eat, we all stand in a circle, hold hands, listen to Doug’s blessing, and finish in a collective “amen”, feeling quite naturally at home and at ease with one another.

Kwaku and Arafat both came to the United States seeking the protection of political asylum. Fearing for their lives for different reasons, they both left their country on a plane headed to Brazil where they would begin their journey on foot…all the way up through Central America to the US/Mexico border. It’s there that they asked for asylum.

In writing this story, I attempted to look up how many miles their journey took them – walking from Brazil to Tijuana. Google Maps tells me “walking route not available”.

When I ask them, Kwaku and Arafat have no idea how many miles it was; for Arafat, the journey took about three months, for Kwaku it took four months. Over our lunch at the McGlashan’s they share with us a bit about the journey, naming off the countries they passed through as if it’s a geography quiz: “Brazil, Ecuador, Columbia…”

Every time I listen to an asylee recount the story of their journey to the US, without fail they each grow quiet when they speak of Panama – “The jungle…you have no idea what I have seen there…”

Along the border of Columbia and Panama lies the Darién Gap, a nearly 60-mile section of dense rainforest. For more than a century, humans have tried to tame the jungle in the Darién Gap, but the jungle has consistently rejected their efforts. This portion of the trek north for asylum seekers is by far the most perilous: those on the journey blindly follow a path through the jungle for days, hardly daring to stop and sleep for fear of what might come upon them. For days they push on: “you can’t stop, you just have to keep walking.” Some migrants carry a bag of sugar with them on this leg of the journey, eating spoonfuls to keep them awake and moving. Robbers, drug traffickers, smugglers, animals and the elements can meet you on the path…it’s better to move through as quickly as possible.

The journey through the jungle crosses wide rivers, two mountains and is strewn with discarded items that migrants who have come before deemed too much to carry. The way is also marked by graves. Arafat keeps his eyes on his plate while he tells me of one woman he journeyed with being bitten by a poisonous snake. “We didn’t have any medicine”, he explains. He describes another night in the jungle when their group was ambushed and searched for money and valuables. He smiles a bit proudly as he recounts to us how he had split up his money between the lining of his hoody and inside his shoes so as to evade a search like this one.

Kwaku’s journey to the US took a month longer than Arafat’s, owning to the fact that in one country, police intercepted him and deported him back to a neighboring country. For most people, this set back is too demoralizing, Kwaku explains. Many people have struggled on the journey too much and feel they don’t have the energy or courage to retrace their steps. They give up and retreat back home, resigning themselves to the danger awaiting them there. But for Kwaku, he pressed on.

As he recounts a bit of his journey, it reminds me of stories from the underground railroad: a kindhearted stranger offers shelter for the night and bread for the next day’s journey; a bus is pulled over and searched because passengers explained to police that there are “black men” on board. And one puzzling story in which a border patrol agent slips him a piece of paper with Spanish scribbled on the back. He’s quickly told to show this paper to agents if he’s detained at the next border, but he forgets this prompt and sits for several hours in a jail not sure if this is the end of his journey. Suddenly remembering the paper, he shows it to agents and is freed to continue on his journey. To this day, he’s not sure what was written on the paper.

Having made it to the US border, Kwaku and Arafat both began the process of seeking asylum, a process which involves being handcuffed and taken to a detention facility. Both expressed to me their shock around this treatment. Arafat motions to his wrists and ankles explaining how he didn’t imagine that in the US he would feel like a criminal. After waiting months in the Northwest Immigration Detention Center – a facility where the lights are never turned off, even for sleeping, and you’re paid $1 a day for your work – both Kwaku and Arafat won their cases, were granted asylum, and allowed to begin their lives in the US.

Through World Relief’s Asylee Resettlement program, they both worked with a caseworker to secure housing, apply for documents and become oriented to their new community. They enrolled in English classes, employment services, and luckily for the McGlashans, were open to meeting other Americans through the Cultural Companion program.

Both Kwaku and Arafat now work as security guards at a prominent Seattle security company and balance hectic schedules of night shift jobs and college classes. Kwaku has already been promoted at his job and Arafat was offered a promotion, but in wanting to give the company his best, he decline the offer explaining that he wanted to improve his English before taking on the position. True to the example other asylees have set before them, Kwaku and Arafat are incredibly hardworking and jumped right in to the work of rebuilding their lives.

Before meeting Arafat, Doug and Lisee had never met an asylee before, let alone fully knew what the term meant. Over lunch, we ask about their experience through all of this, what it’s been like to build this relationship which started as a formal “cultural companion match” and has grown into an authentic relationship.

“We’ve received so much more than we’ve given…how rich it is for us, to have their stories as part of our stories now” Lisee explains.

Addressing Kwaku and Arafat, Doug explains, “It’s inspiring, because when you hear what you’ve been through to get here, I can’t imagine what it took to survive that. And then when you arrive here, it’s so gratifying to see how you take on your dreams and ambitions. It’s an honor to watch you become who you want to be….it’s wonderful to be together like a family and watch our relationship grow.”

What’s going on at the border?

The following is a reflection written by John Miller, Immigration Specialist at World Relief Seattle. He is accredited by the Department of Justice to practice immigration law.

Things have felt a little different for me since I’ve been back from Mexico. It’s hard now to read these ideologically-charged news stories about “The Wall” and “The Border” without seeing the faces of the people I met while I was in Tijuana.

I went to Tijuana to meet up with three other World Relief staff members from three different World Relief offices around the country. We convened near the border to partner with a local organization called Al Otro Lado, one of the leading organizations on the ground in Tijuana that provides support to people approaching the US border to apply for asylum. The four of us were selected for this trip because our expertise and credentials with practicing immigration law.

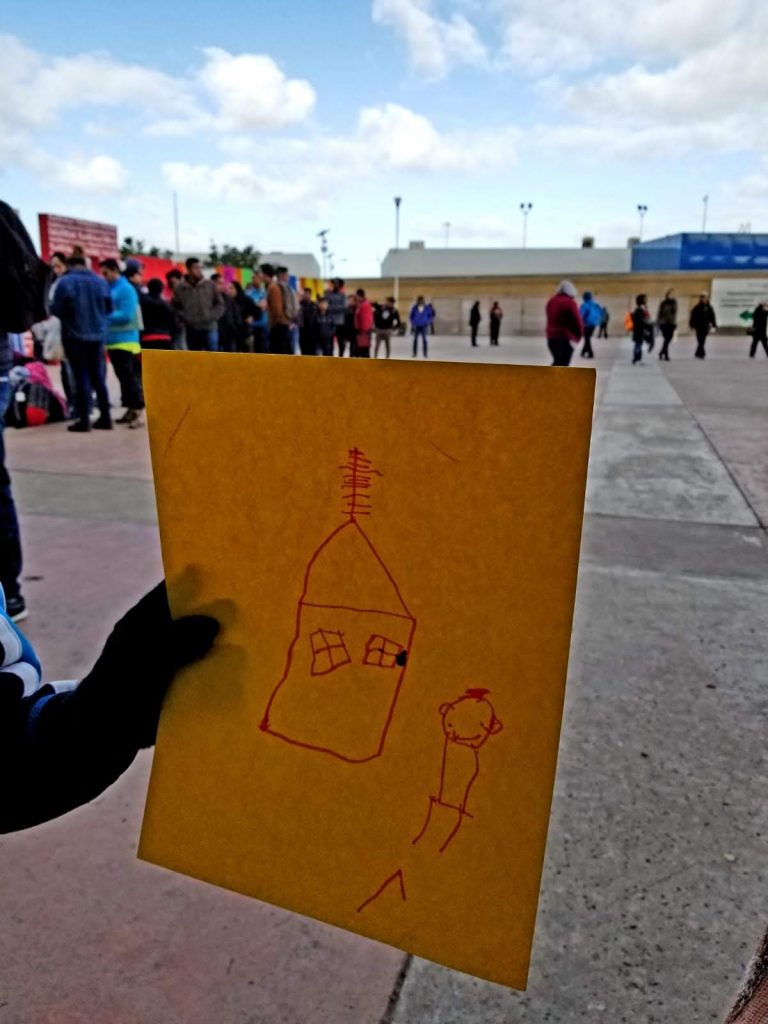

Each morning, we would enter El Chaparral, the infamous plaza in Tijuana, located directly before the border crossing point of entry. I use the word “infamous” because it has essentially become a massive waiting room. But in this particular waiting room, one doesn’t pull a number from a small machine and wait a few hours before speaking to someone. There aren’t chairs to sit on, and there isn’t a receptionist waiting there to help you. In fact, there aren’t staff there to assist you at all. El Chaparral is an uncovered slab of concrete where people from all over the world wait, for weeks or months, before they are allowed to approach the US border to apply for asylum.

Five years ago, if you went to any point of entry along the border to present yourself to US immigration officials and ask for asylum–the “correct way,” as laid out by US immigration law–you would have been taken into the custody of the U.S. government until the next decision had been made on your case. Today, if you go to the border to apply for asylum, you will be told to turn around and put your name on a list to get a number, or even told that you can’t apply there and you need to find another point of entry. You will likely end up in Tijuana, where you would spend the next 3-9 weeks of your life sitting around in El Chaparral, waiting for your number to get called.

This business of getting a number before applying for asylum is a recent phenomenon. U.S. immigration law has stated for decades that any person can approach any border crossing point of entry to apply for asylum. Turning someone away who fears for their life and may have a viable asylum claim is a violation of our own law. This new process also forces people to go through Mexican border officials first in order to gain access to U.S. authorities, which can put people, especially those from Mexico, in increased danger of exploitation and persecution. The physical list being passed back and forth between Mexican and American authorities is ripe for bribery and exploitation.

Our team spent the mornings meeting with individuals and families who were moored in El Chaparral, waiting on their numbers. We gave short presentations on the basics of asylum and what to expect after entering U.S. custody. Next, we met with individuals and families to answer further questions. For each person we spoke with, we gave instructions and directions to Al Otro Lado’s office, so that they could come later to get a free orientation and a free consultation with an immigration practitioner. We spent the afternoons doing one on one consults, learning each person’s story and discussing the exact claim to asylum that the person may or may not have.

One man I met with, who I’ll call Francis, had fled his country in western Africa just two weeks prior to our meeting. When I started our meeting by asking him what country he was from, the whole story came pouring out, the living nightmares that he had survived, and how he escaped. Everything he shared was so fresh. I asked Francis how long he had been waiting in Tijuana. When he told me that he arrived in Tijuana that very morning, it dawned on me: I was the very first person to hear what had happened to him. Here he was, on the other side of the world from his birth place, without anyone he knew, no Spanish ability, no legal authorization to work in Mexico, and no sense of how long he would have to wait before applying for asylum, and I, a total stranger, was the first person to hear his story. I was amazed by his resilience, conviction, and his willingness after everything to stand up for what is true and right. While it was difficult to hear the torture he had endured, I was able to share some good news: the supervising attorney and I both agreed that he had a very strong case. “Your case is very strong,” I encouraged Francis, “and the immigration judge may agree with us that you meet the legal definition of asylum on multiple grounds. Keep moving forward and don’t lose hope.”

I can’t read the news anymore without thinking of Francis’s face: the tears in his eyes, and the strength in his eyes. I think of the Guatemalan family I met in the plaza: the fear in the young mother’s voice, pleading with me to know if there was any way for the family to stay together after passing into US custody, and her fierce, protective love for her kids. I think about the newlyweds from Honduras and the single dad from Cameroon and the nineteen-year-old nursing student from Russia and the minor from Nicaragua who was traveling by herself. These aren’t just news stories about policies, budgets, or political division: they are stories of real people.

The situation is dire, but there is hope. There are organizations like Al Otro Lado who are on the ground, meeting, educating, and equipping the long line of asylum seekers in Tijuana. There are World Relief offices around the country supporting asylum applicants, both inside and outside of immigration detention. And above all, I know that the people I met in Tijuana are some of the strongest people I’ve met, and that gives me hope.

For many immigrants, arrival to America is not the end of navigating the complicated U.S. immigration system. That is why our office has expanded our Immigration Legal Services team from one to three full-time staff who are Department of Justice accredited over the last year. Assisting refugees, asylees and immigrants with work authorization, family reunification, and citizenship are just a few of the services this hard-working team does for newcomers. With your support, we are able to offer these services either pro-bono or at reduced rates to those in need.

A Myth of Scarcity

The following reflection is written by World Relief Seattle intern, Aubrey Payne. Aubrey spends her days with World Relief accompanying people on appointments, helping out in English class, building relationships with newcomers, and otherwise assisting in the resettlement process.

Every day that I spend with the participants at World Relief, I am reminded of the generosity that comes from God’s abundance.

Recently, I took a single mother from Afghanistan to a gruelingly long appointment at the Department of Social and Health Services. She and I met with three different employees in a process that took over 5 hours, only to find out that she was being denied food stamps. The baby was tired and cranky, as were we, and the mother broke down in tears. The weight of her situation–as an immigrant with very little money, trying to start a new life for herself and her baby–started to sink in. We got in the car to drive home. In an expression of gratitude for my time, she gave me a handful of chilgoza–a type of pine nut found in Afghanistan and which costs about $20 per bag.

In The Liturgy of Abundance, the Myth of Scarcity, Walter Brueggeman writes, “What we know about our beginnings and our endings, then, creates a different kind of present tense for us. We can live according to an ethic whereby we are not driven, controlled, anxious, frantic, or greedy, precisely because we are sufficiently at home and at a peace to care about others as we have been cared for.” The truth is, many people will never feel like they have enough. We place a high value on work and busyness in America, often believeing that we do not have enough time or resources to care for others the way Jesus did.

The generosity demonstrated to me by a tired Afghan mother is the kind of generosity I see every time I meet with the refugees and immigrants who come through World Relief’s doors. Because a belief in God’s abundance far exceeds the restrictions imposed by the economy or personal finances, this woman felt moved to share a cultural delicacy with me, even though she had so little to offer. When we believe in the good news of God’s abundance, there are no more excuses for living a greedy and un-neighborly life. If we believe in a God that loved the world into generous being, then we can live in the knowledge that there is enough to go around to everyone. It is a different kind of present tense. We can be at peace to care about others as we have been cared for, even if that just looks like a handful of precious pine nuts.

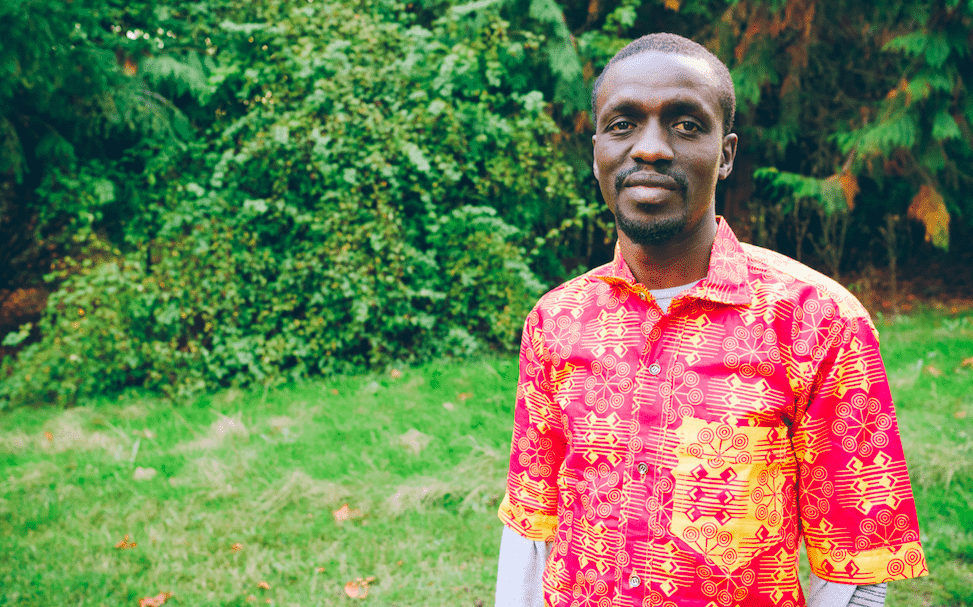

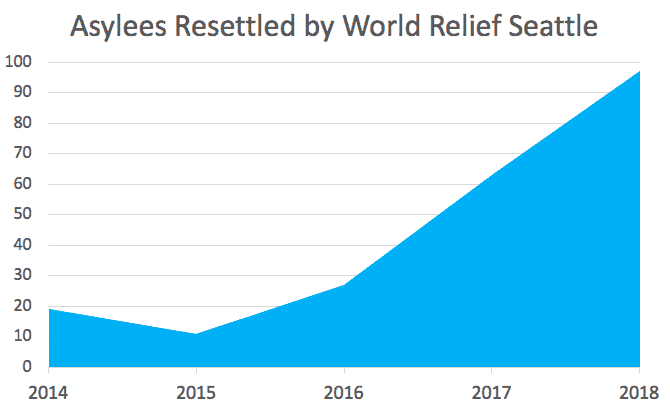

Asylees in Seattle

After spending months in the Immigration Detention Center in Tacoma, Mamadou still had more waiting to do. A federal judge had granted him asylum, and he was now free to start his new life here in America, but his life wasn’t whole. He fled political persecution in Guinea 4 years ago when a gathering at his home was violently dispersed. Staying meant torture and the possibility of death. Fleeing meant leaving behind his young daughter and pregnant wife. It was a choice nobody should have to make. When describing that decision, Mamadou shared that, “I was leaving my poor family in terrible fear.” We are seeing this kind of decision forced upon thousands of people who have to choose between safety and remaining in their country.

Home by Warsan-Shire

“No one leaves home unless

home is the mouth of a shark

you only run for the border

when you see the whole city running as well…”

Mamadou’s desperate journey took him halfway around the globe. His flight to safety is similar to the journey of the asylum seekers currently at the border that are being shown on the news right now. Their stories are often politicized rather than understood as a complex choice made by people in desperate situations.

This global crisis becomes a local reality when people like Mamadou turn themselves in at the border and are then handcuffed and transported up I-5 to the detention center in Tacoma. Thousands of people passed through that facility this year, and about 80% of them were deported back to their country of origin. We have seen a great increase in the number of people being detained, and the number of people in need of encouragement, care, and connection to resources. Our volunteers came alongside 4,025 individuals while they were in detention this past year. some of whom were parents who had bee separated from their children at the border.

You have to understand,

that no one puts their children in a boat

unless the water is safer than the land

no one burns their palms

under trains

beneath carriages

no one spends days and nights in the stomach of a truck

feeding on newspaper unless the miles travelled

means something more than journey.

no one crawls under fences

no one wants to be beaten

pitied

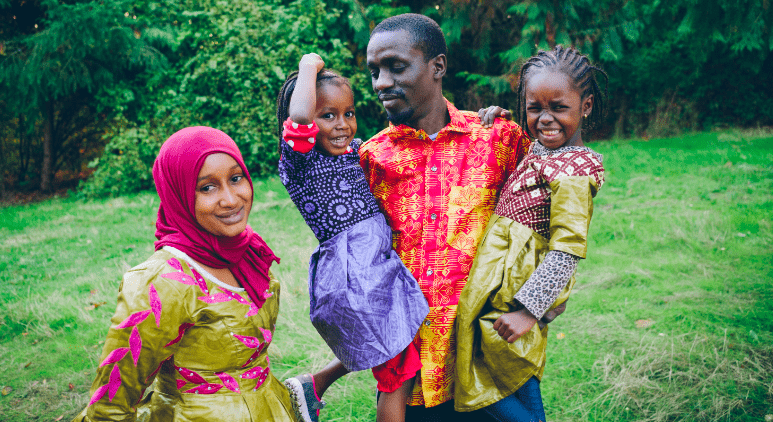

Finally, this summer, Hassatou and the two young girls arrived to Washington. Mamadou met his youngest for the first time. He held his wife at last. His family was finally whole and safe. Their journey is not over though: Hassatou and the girls are beginning to learn English, Mamadou is making ends meet to afford a bigger apartment for his family, and they are together building a new community of friends and neighbors.

Will you join us helping newcomers like Mamadou, Hassatou, and their girls meet these challenges?

The most powerful teacher

The following is a reflection by Beth Watkins, World Relief Seattle Resettlement Intern.

I’ve thought a great deal about my hometown lately.

Being a fairly recent Seattle transplant, perhaps it’s simply homesickness finally kicking in. Perhaps the stark differences in landscape, the lack of familiar faces, and the infamous “Seattle freeze” are finally beginning to wear on me. Whatever the reason, home has been on my mind.

I come from a small midwestern town in southern Illinois with a population of about 500 people. It’s a largely agricultural community. Most people over the age of 60 still speak at least a little German. Once a year my entire town gets together to make and jar apple butter. Everyone is at least distantly related– there are probably a total of ten last names in the whole town. It’s a place that feels far removed from the rest of the world.

Last week I got to sit in on World Relief’s sewing class for the first time, and for a few hours, I was transported back to the Midwest, to quilting circles in church basements (albeit with a little more Dari than I remember being spoken at home). As I talked with the students and volunteers, I thought of my grandmother, who has hand-stitched multiple quilts for each of her children and grandchildren. It was so easy for me to picture her in this room of women, talking about fabric patterns and bragging about grandchildren. But as easy as it is to picture her there, I don’t think my grandmother will ever sit in a room full of Afghan women. Not because she doesn’t want to– she often expresses interest in my work at World Relief, asking about the people I’ve met and the things I’m learning– but because she lives hours from a major city with any detectable level of diversity. She’s simply unlikely to ever encounter a refugee in her daily life.

It’s easy for me to become angry at my community for being ambivalent or negative towards refugees…until I remember that my most powerful teacher has been my firsthand experiences with refugees themselves. These are experiences that many of my family members and neighbors will most likely never have, simply because they don’t have access to them. And while this doesn’t excuse prejudicial attitudes and behaviors, it does contextualize them. How can you come to care for someone you have never met, who is simply a theoretical idea, a conveniently distant scapegoat for economic disparity and a rapidly evolving cultural landscape?

My hope for my community is that somehow, eventually, they become personally connected to refugee communities. I hope they are allowed the same opportunities I’ve been given to sit with refugee families, to hear their stories, to stumble over language barriers, to share food and laughter and time together, to grow out of prejudice and into relationship. I don’t yet know what this looks like or how to make it happen–how to overcome physical distance and, in many cases, deep prejudice. I don’t know how these experiences will happen, but I know that the prejudice in my community will not change until they do. Until I find a way to bridge this gap, I can convey my own experiences and at least act as a small window into the lives of the refugees they have yet to encounter. I can act as a cultural broker for my own community, an invitation into a new way of being and moving through the world.