Guest Contributors

Time is running out for many Ukrainians living in limbo in the U.S.

by Michael Kovbanyuk //

“In June, Russia launched its missiles at Ukraine in two separate pre-dawn attacks leaving 23 dead and many more injured. While the war in Ukraine may be fading in the minds of Americans, these recent attacks serve as a painful reminder that countless Ukrainians still live in fear for their lives every day.

Since the war began in 2022, more than 118,000 Ukrainians have found safe refuge in the United States under Uniting for Ukraine. This program, established by the U.S. government last year, grants Ukrainians seeking refuge temporary parole status in the U.S. for two years. However, it leaves vulnerable people in need of refuge in limbo while they wait to learn their fate regarding permanent residency. …” Read the full piece at the Greensboro News & Record

From DRC to the 253: A blacklisted, exiled journalist hasn’t given up working for a better Congo

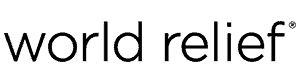

At his newfound home in Tacoma, Washington, Antoine Roger Bolamba has watched Chris Cuomo criticize Donald Trump on live TV. Seven years ago, working for Radio-Télévision Nationale Congolaise, the national TV station of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, he could not have dreamed of criticizing his president.

“In my home country, you will not finish your program,” he said. “You will see military people; police will come.”

Bolamba narrowly avoided this very fate. Achieving his lifelong dream, he held the spotlight as a primetime anchor for Congo’s national TV station. But when the country’s lack of journalistic freedom became a personal reality, he was confronted by a terrible choice.

A Crisis of Press Freedom

Covering the vast, resource-rich Congo River Basin, Congo is the second largest country in Africa. Several local kingdoms dominated the area before Belgian colonization during the 19th and 20th centuries. Despite gaining independence in 1960, the nation has been plagued by constant internal and external conflicts and subsequent humanitarian crises.

Bolamba was born in Kinshasa, Congo’s capital, and raised by Catholic charismatic parents. When he was still young, Bolamba knew he wanted to become either a priest or a journalist. He wanted to serve God and inform people.

from an educational nonprofit he started in Congo. (Photo/Daniel Hart)

He interned for a private TV broadcaster while studying journalism at the Catholic University of Congo. In 2010, Bolamba started working for the national TV station. Within six months, he was presenting the 8 p.m. news for the country’s largest TV audience.

He didn’t stop there. In 2012, he was hired as a press attaché for the country’s Planning Ministry. His work took him around the world. In 2013, he created a video on investment opportunities in Congo and presented it alongside the Planning Minister at the U.S.-Africa Business Summit in Chicago. In 2014, he traveled to Mexico City to argue to the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative that Congo’s mining industry was making meaningful progress toward benefiting the country’s citizens. That same year, he covered a summit in Belgium for the international Congolese diaspora.

For all his success, he was very aware that all was not well for journalists in Congo.

Reporters Without Borders, an international nonprofit that advocates for press freedom, ranked Congo 149 out of 180 in its 2021 World Press Freedom Index. Also this year, Freedom House, a U.S. government-funded research institute, gave Congo a 20 out of 100 ‘not free’ score for political rights and civil liberties.

Bolamba described journalism in Congo as neither free nor independent. Known locally as coupage, payment from sources is an everyday occurrence and practically journalists’ only form of income.

“You are depending on the politician or on people who need you to pass their message,” Bolamba said. “So because you get paid from there, you cannot be objective.”

In addition to the lack of financial independence, Bolamba said he and other journalists were watched closely by government officials as they presented the news, especially when they spoke about the government. He knows many colleagues who have been imprisoned as a result of their work. Others have died under mysterious circumstances. Bolamba learned to be careful what he ate or drank, especially with politicians. In taxis, he always sat beside the door, not between other passengers. He took care to protect his reputation from defamation, avoiding the appearance of anything that might be professionally unacceptable.

In 2012, the country’s information minister accused another politician of having sex with a minor, and Bolamba investigated. Although the politician was jailed, Bolamba’s coverage cast the allegations into doubt. He doesn’t know for sure, but he suspects that his work on this story may have led to what came next.

The Crash

One day in 2013, the TV station’s human resources director quietly showed Bolamba a letter that the director of the station had sent to several government officials. The HR director wouldn’t give Bolamba a copy, fearing for his own safety. The letter stated that Bolamba was working against the ligne editorial, the editorial policy the government expected to hear on national TV. It claimed that Bolamba was giving too much airtime to the opposition. The HR director warned that Bolamba’s director was trying to destroy his reputation and that he was in danger of being imprisoned or killed.

As Bolamba read the letter, he was shocked and bewildered. By the time he left the office, he knew he could not stay in Congo.

Eventually, an auditor who Bolamba knew was able to surreptitiously secure a copy of the letter for him. He asked friends and colleagues for help and advice. Over and over, they told him the same thing: your life is in danger; you have to leave. Fortunately, Bolamba had a U.S. visa from his previous work trips. However, his sons and Claudia, his wife, did not. She implored him not to leave.

“‘It looks like something bad is coming, so I need to leave,’” Bolamba recalled telling her. “She insists, ‘Don’t do that! I have kids.’”

As Bolamba remembered agonizing over the possibility of leaving his wife and four sons behind, he stopped, unable to continue for several minutes. He silently wiped away tears triggered by the memory of that separation.

Slowly, in a low, constricted voice, he began his story again, recounting how Claudia left with the children for another part of the country, far from Kinshasa.

“In normal time, I could not accept that my spouse and kids live there,” he said. “No water, no electricity. So no car. No good school.” He said the decision still haunts him.

On March 1, 2015, compelled by the real possibility of arrest or murder, Bolamba left the country.

“I arrived here in Seattle with nothing,” he said. “So I restarted a new life from the crash.”

He stayed with various friends for weeks or months at a time. He sent documentation of his experience, including the letter that had blacklisted him, to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. They sent him a work authorization card to use while his case was considered. Over the next few years, Bolamba took jobs as a security guard, a recycling sorter and a Lyft driver.

In 2018, he received the news he had been hoping for: he had been granted asylum. He received his Green Card, confirming his status as a permanent U.S. resident. Then, he went to World Relief, looking for help to bring his family from Congo. World Relief’s Immigration Legal Services team provided a cheaper option for help with submitting the needed forms. That year, Bolamba’s wife and sons were able to join him in Seattle. Bolamba thanked God for reunifying his family.

At the same time, Bolamba said he continues to grieve what he lost. Since arriving, he has worked to survive, not to pursue journalism. He wonders if he will never do his dream job again.

“I was thinking about that today again,” he said. “If I didn’t take that decision to be proactive, I don’t know what should happen. I don’t know. But I took this action. Today I can live with my spouse and my kids – far away from my business, my job, my family, my friends.”

Start Somewhere

In spite of his exile, Bolamba remains committed to the journalistic ideal. While he currently works as a caregiver, he is eager to return to reporting. In March, he received certification as a public relations consultant and completed online courses in human rights and diplomatic protocol. He is a member of the Seattle Association of Black Journalists.

Looking to the future, he is working to build a public relations channel called Pano 5 as well as a geopolitical podcast focused on Congolese politics, poverty and natural resources. He has plans for a nonprofit, African School of Family Wellbeing, that would work to improve life for Congolese families.

“I don’t like to count on people anymore,” he said. “I prefer to count on God and listen to myself, what God is telling me to do, go where God is telling me to go.”

He said his accent and lack of vocabulary pose significant challenges.

“I need to start somewhere because it’s kind of a passion for me. But a passion that broke,” he said.

The threat of violence, a harrowing separation from his family and the struggle to rebuild a life far from home shattered Bolamba’s dream. Yet here on the other side of the world, he is reassembling his vision piece by piece. Bolamba is doing all he can to break the pattern of violence and political repression that has plagued his homeland for decades. He said he hopes to see a president legitimately elected through the democratic process.

“My hope is that one day, the Congo will be living in peace, everywhere in the country,” he said.

Daniel Hart is a Seattle-based journalist who writes about politics, immigration, and religion. In 2020, he completed a refugee resettlement internship with World Relief Seattle.

Both Can Be True

Several months ago, a counselor said something that has stuck with me. She told me, “Both can be true.” I have held onto these words in the past few months as a tangible way to remind myself of the tension and the reality in our day-to-day world.

For the past couple years, my husband and I have been focused on building a business in his home country of Guatemala, seeking to provide employment for local residents. But, due to COVID-19, all of our work was cancelled and capital quickly dried up. As a result, we’ve had to let go of the business. The grief has been so real. And yet, I struggled to know how to feel it in the midst of a global pandemic and economic recession when our family is healthy and employed. But I can be grateful for what I have and disappointed about what I’ve lost. Both can be true.

In June, Rayshard Brooks was killed by police at my neighborhood Wendy’s. The restaurant was later burned down. On the 4th of July, I shared how I can be patriotic and want our country to address her glaring need for real change. Both can be true.

Next week, my kids “start” school. This weekend, we’re building a workspace in our living room. Moms and dads and teachers all over the country are battling a million emotions about this topic. I am allowing myself to rest in the nuanced tension. I can be concerned about my state’s rising COVID numbers and grieve that my kids aren’t going back to school. I can care about the physical health of my community and also about its mental health and economic well-being. Both can be true.

Last week, the Department of Homeland Security issued a new memo impacting “Dreamers,” immigrants brought to the U.S. as children. On one hand, I’m relieved that the administration has (at least for now) decided not to again attempt to fully rescind DACA, which news reports had suggested was coming. On the other hand, the memo means new hardships for DACA recipients, including filing renewals and paying hefty fees every year, rather than every two years, and barring new applicants to DACA, which we’d presumed based on the June Supreme Court decision would re-open. It’s a relief and it’s frustrating. Both can be true.

Too often, we are pressured to reduce life to binary choices with simple answers. Are you for or against? Left or right? Which side are you on?

But we do not have to neglect the nuance. I honestly think it’s inauthentic to pretend we have no doubts, no questions, no wavering or wondering. It’s also dismissive of those around us to assume that because they share one point of view that it’s the sole perspective they have on the issue.

I recently had a conversation with someone who had an influence on my childhood faith. When she heard I’d written a book, she asked what it was about. I tried not to answer. But eventually, I told her it was about immigration and faith. She immediately asked if I was “all about open borders.” I may have sighed.

I can care about reasonable border security and advocate for making a safe place to welcome asylum seekers. I can believe in the rule of law and want to see Dreamers have a permanent solution. I can support people going through the immigration process “the right way,” while also acknowledging that we’ve made “the right way” very narrow and there’s room to make it simpler and more welcoming. These things can all be true.

We benefit from holding the right amount of tension. It’s good that we have more than one political party. It’s helpful that people have different points of view than our own. These push and pull factors in society help us foresee challenges we otherwise wouldn’t, think creatively, and problem-solve together. I believe we have an opportunity to be an example of holding space for the both/and. Sometimes two truths that others may want to be contradictory hold hands and help us to walk forward with strength.

Both can be true.

Sarah Quezada is a writer, speaker, and advocate. She has a master’s in sociology and wrote Love Undocumented: Risking Trust in a Fearful World. She also oversees the fast-growing online community Women of Welcome, a project of World Relief and the National Immigration Forum. She and her husband Billy live in Atlanta, Georgia and are raising two bicultural and trilingual-ish kids. Find Sarah on Instagram at @sarahquezada or her website sarahquezada.com.