Long-form Stories

From DRC to the 253: A blacklisted, exiled journalist hasn’t given up working for a better Congo

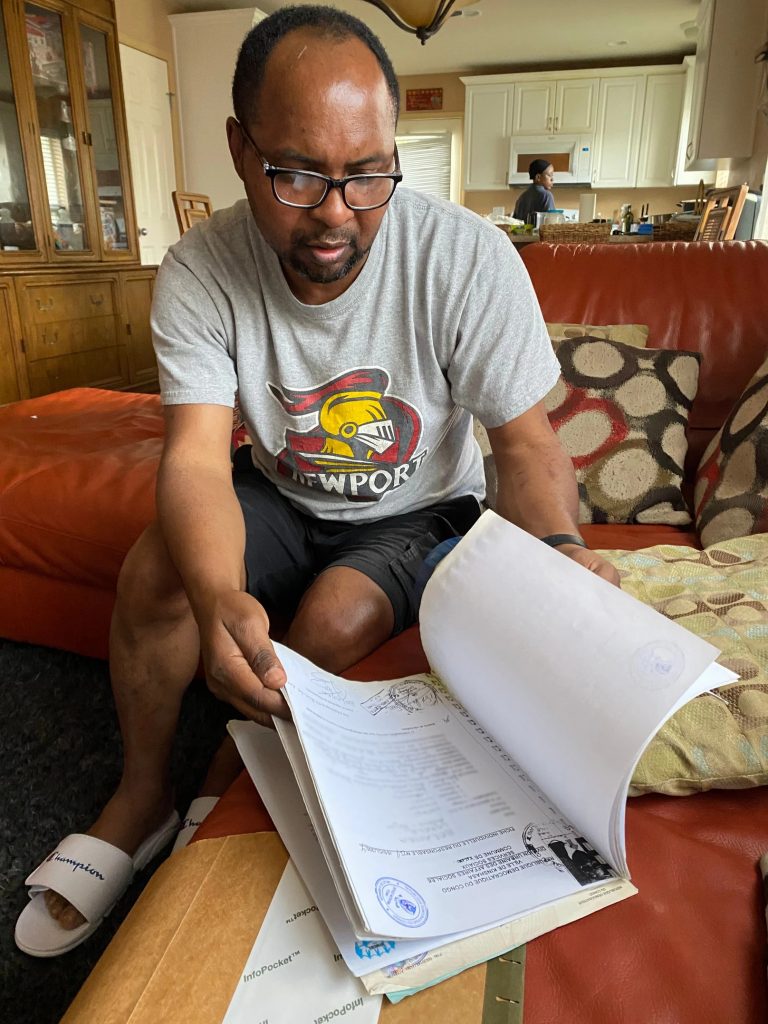

At his newfound home in Tacoma, Washington, Antoine Roger Bolamba has watched Chris Cuomo criticize Donald Trump on live TV. Seven years ago, working for Radio-Télévision Nationale Congolaise, the national TV station of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, he could not have dreamed of criticizing his president.

“In my home country, you will not finish your program,” he said. “You will see military people; police will come.”

Bolamba narrowly avoided this very fate. Achieving his lifelong dream, he held the spotlight as a primetime anchor for Congo’s national TV station. But when the country’s lack of journalistic freedom became a personal reality, he was confronted by a terrible choice.

A Crisis of Press Freedom

Covering the vast, resource-rich Congo River Basin, Congo is the second largest country in Africa. Several local kingdoms dominated the area before Belgian colonization during the 19th and 20th centuries. Despite gaining independence in 1960, the nation has been plagued by constant internal and external conflicts and subsequent humanitarian crises.

Bolamba was born in Kinshasa, Congo’s capital, and raised by Catholic charismatic parents. When he was still young, Bolamba knew he wanted to become either a priest or a journalist. He wanted to serve God and inform people.

from an educational nonprofit he started in Congo. (Photo/Daniel Hart)

He interned for a private TV broadcaster while studying journalism at the Catholic University of Congo. In 2010, Bolamba started working for the national TV station. Within six months, he was presenting the 8 p.m. news for the country’s largest TV audience.

He didn’t stop there. In 2012, he was hired as a press attaché for the country’s Planning Ministry. His work took him around the world. In 2013, he created a video on investment opportunities in Congo and presented it alongside the Planning Minister at the U.S.-Africa Business Summit in Chicago. In 2014, he traveled to Mexico City to argue to the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative that Congo’s mining industry was making meaningful progress toward benefiting the country’s citizens. That same year, he covered a summit in Belgium for the international Congolese diaspora.

For all his success, he was very aware that all was not well for journalists in Congo.

Reporters Without Borders, an international nonprofit that advocates for press freedom, ranked Congo 149 out of 180 in its 2021 World Press Freedom Index. Also this year, Freedom House, a U.S. government-funded research institute, gave Congo a 20 out of 100 ‘not free’ score for political rights and civil liberties.

Bolamba described journalism in Congo as neither free nor independent. Known locally as coupage, payment from sources is an everyday occurrence and practically journalists’ only form of income.

“You are depending on the politician or on people who need you to pass their message,” Bolamba said. “So because you get paid from there, you cannot be objective.”

In addition to the lack of financial independence, Bolamba said he and other journalists were watched closely by government officials as they presented the news, especially when they spoke about the government. He knows many colleagues who have been imprisoned as a result of their work. Others have died under mysterious circumstances. Bolamba learned to be careful what he ate or drank, especially with politicians. In taxis, he always sat beside the door, not between other passengers. He took care to protect his reputation from defamation, avoiding the appearance of anything that might be professionally unacceptable.

In 2012, the country’s information minister accused another politician of having sex with a minor, and Bolamba investigated. Although the politician was jailed, Bolamba’s coverage cast the allegations into doubt. He doesn’t know for sure, but he suspects that his work on this story may have led to what came next.

The Crash

One day in 2013, the TV station’s human resources director quietly showed Bolamba a letter that the director of the station had sent to several government officials. The HR director wouldn’t give Bolamba a copy, fearing for his own safety. The letter stated that Bolamba was working against the ligne editorial, the editorial policy the government expected to hear on national TV. It claimed that Bolamba was giving too much airtime to the opposition. The HR director warned that Bolamba’s director was trying to destroy his reputation and that he was in danger of being imprisoned or killed.

As Bolamba read the letter, he was shocked and bewildered. By the time he left the office, he knew he could not stay in Congo.

Eventually, an auditor who Bolamba knew was able to surreptitiously secure a copy of the letter for him. He asked friends and colleagues for help and advice. Over and over, they told him the same thing: your life is in danger; you have to leave. Fortunately, Bolamba had a U.S. visa from his previous work trips. However, his sons and Claudia, his wife, did not. She implored him not to leave.

“‘It looks like something bad is coming, so I need to leave,’” Bolamba recalled telling her. “She insists, ‘Don’t do that! I have kids.’”

As Bolamba remembered agonizing over the possibility of leaving his wife and four sons behind, he stopped, unable to continue for several minutes. He silently wiped away tears triggered by the memory of that separation.

Slowly, in a low, constricted voice, he began his story again, recounting how Claudia left with the children for another part of the country, far from Kinshasa.

“In normal time, I could not accept that my spouse and kids live there,” he said. “No water, no electricity. So no car. No good school.” He said the decision still haunts him.

On March 1, 2015, compelled by the real possibility of arrest or murder, Bolamba left the country.

“I arrived here in Seattle with nothing,” he said. “So I restarted a new life from the crash.”

He stayed with various friends for weeks or months at a time. He sent documentation of his experience, including the letter that had blacklisted him, to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. They sent him a work authorization card to use while his case was considered. Over the next few years, Bolamba took jobs as a security guard, a recycling sorter and a Lyft driver.

In 2018, he received the news he had been hoping for: he had been granted asylum. He received his Green Card, confirming his status as a permanent U.S. resident. Then, he went to World Relief, looking for help to bring his family from Congo. World Relief’s Immigration Legal Services team provided a cheaper option for help with submitting the needed forms. That year, Bolamba’s wife and sons were able to join him in Seattle. Bolamba thanked God for reunifying his family.

At the same time, Bolamba said he continues to grieve what he lost. Since arriving, he has worked to survive, not to pursue journalism. He wonders if he will never do his dream job again.

“I was thinking about that today again,” he said. “If I didn’t take that decision to be proactive, I don’t know what should happen. I don’t know. But I took this action. Today I can live with my spouse and my kids – far away from my business, my job, my family, my friends.”

Start Somewhere

In spite of his exile, Bolamba remains committed to the journalistic ideal. While he currently works as a caregiver, he is eager to return to reporting. In March, he received certification as a public relations consultant and completed online courses in human rights and diplomatic protocol. He is a member of the Seattle Association of Black Journalists.

Looking to the future, he is working to build a public relations channel called Pano 5 as well as a geopolitical podcast focused on Congolese politics, poverty and natural resources. He has plans for a nonprofit, African School of Family Wellbeing, that would work to improve life for Congolese families.

“I don’t like to count on people anymore,” he said. “I prefer to count on God and listen to myself, what God is telling me to do, go where God is telling me to go.”

He said his accent and lack of vocabulary pose significant challenges.

“I need to start somewhere because it’s kind of a passion for me. But a passion that broke,” he said.

The threat of violence, a harrowing separation from his family and the struggle to rebuild a life far from home shattered Bolamba’s dream. Yet here on the other side of the world, he is reassembling his vision piece by piece. Bolamba is doing all he can to break the pattern of violence and political repression that has plagued his homeland for decades. He said he hopes to see a president legitimately elected through the democratic process.

“My hope is that one day, the Congo will be living in peace, everywhere in the country,” he said.

Daniel Hart is a Seattle-based journalist who writes about politics, immigration, and religion. In 2020, he completed a refugee resettlement internship with World Relief Seattle.

Abdul and Yao: A Welcomer is Welcomed

World Relief’s work would not be possible without the volunteers who give their time to connect with refugees and immigrants. From airport pickups to youth mentorship, volunteers play a pivotal role in helping families adjust to life in the United States. However, some volunteers might worry, “What if we’re too different? Will it be awkward if we don’t have anything in common?” World Relief’s volunteer tutor, Yao, shared a story about how he wondered the same – until the family of the boy he was tutoring showed him the power of a warm welcome.

The Gift of Volunteering

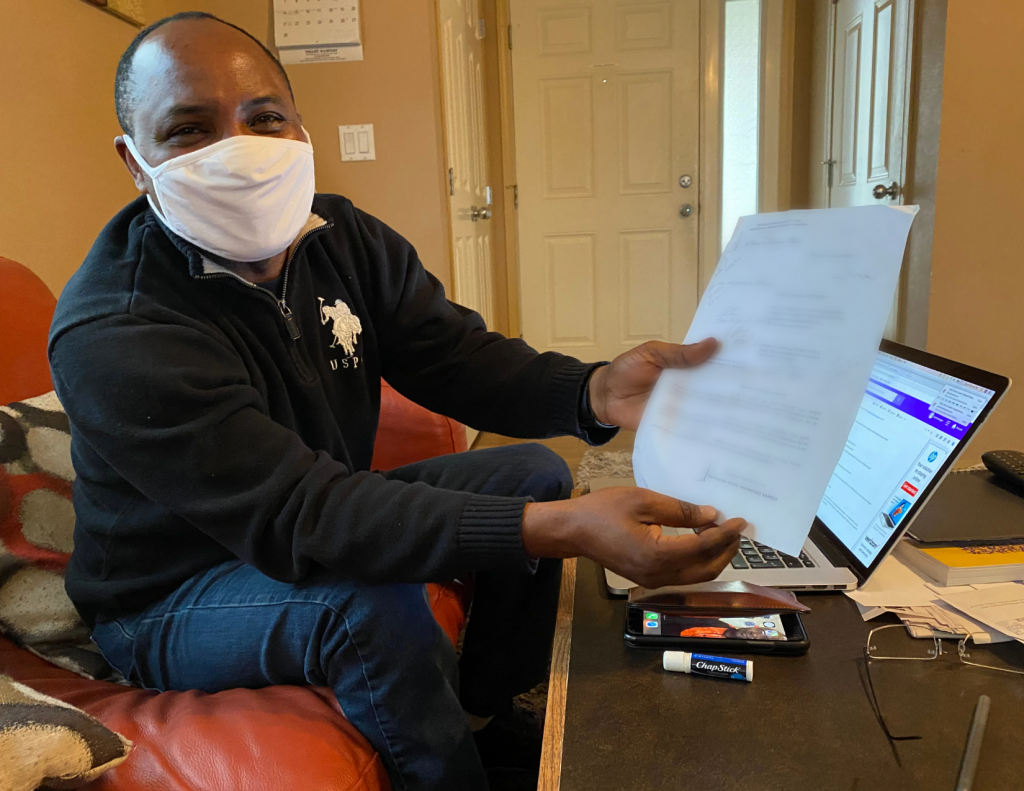

When you join World Relief as a volunteer, it is your gifts, abilities, and passion to make a difference that helps you connect with families and individuals rebuilding their lives in a new country. A World Relief volunteer tutor, Yao, was no different. As a trained nurse and child development worker from a country in West Africa, Yao came to the United States on a scholarship to gain further education in psychology and counseling. He brought those skills to his work as a volunteer tutor with World Relief, where he met the family of a little boy named Abdul.

North Meets South

Abdul and his family came from Yao’s home country in West Africa – but their circumstances looked very different. While Yao was in the U.S. to study and prepare for a life in ministry, Abdul and his mother came to the United States four years after Abdul’s father Jacob arrived seeking asylum. Though they shared a common homeland, Yao and Abdul were also from different regions of the country and spoke distinct languages. In fact, relations between the north and south regions are strained by political and ethnic tensions.

Knowing this, Yao’s worry was one that you and many other volunteers might also have. What would the family think of Yao, someone from their country but who had a very different cultural heritage? What if meeting Abdul and his family was tense or awkward?

Yao shared his concern, saying, “In my country, there is an unspoken thing when you connect with somebody from the north. Either they are expecting you to treat them differently, or you yourself start treating them differently.”

However, Yao joined countless volunteers in World Relief’s long history of serving immigrants and refugees and nevertheless stepped out in faith to serve. As his story shows, this choice brought him a blessing in return.

Despite his concern, Yao scheduled time with Abdul’s family to meet for the first time. Before launching tutoring sessions, everyone started by introducing themselves. Yao explained that he came from the south part of their country. Abdul and his father Jacob shared that they came from the north. Then Jacob, Abdul’s father, did something surprising. “We didn’t say anything about it right away,” Yao said, “But then Abdul’s dad spoke to me in my native tongue.” In an unexpected turn of events, Jacob became the one offering a welcome – by relating to Yao in his own language. Yao says, “I was thinking, ‘Oh, he spoke to me in my native tongue! That’s amazing!’” After that, the conversation flowed much more easily. To Yao, it was as if Jacob had said, “I embrace your culture!”

From that moment on, the conversation flowed smoothly. According to Yao, “From there, we knew there wasn’t going to be much tension. It was as if Abdul’s parents knew, ‘Okay, this person cares about our kid. There’s not going to be any struggle here.’”

It was if he had said, “I embrace your culture.”

Becoming Family in the Midst of Crisis

When World Relief matches tutors with students, it is with a firm belief that not only will the student’s life and education improve, but the relationship will be transformative for the tutor as well. Volunteers like Yao are examples of that dynamic. After their initial meeting, Yao and Abdul had several tutoring sessions. And then the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

At that time, Abdul’s mother was pregnant, Abdul he had to finish first grade from home, and his father Jacob lost his job.

In the midst of this crisis, the World Relief community of volunteers and donors like you came together to respond. In a coordinated effort, World Relief provided a way for the community to provide food and gift cards to the family, continue Yao and Abdul’s tutoring sessions online, connect Abdul’s mother to an English tutor, and walk with the family as Jacob got a new job doing electrical assembly for air conditioners.

The relationship sparked when World Relief connected Yao to Abdul through the tutoring opportunity that has also continued. From the time that Jacob spoke Yao’s language as a sign of friendship, the relationship between Yao and the family has provided a mutual sense of familiarity and comfort. Even as newcomers, Abdul’s family has extended hospitality and welcomed Yao for dinner several times. In return, they have visited Yao’s home for meals too. “They share news of their family with me, and I share news of my family with them,” Yao says. “We became like a kind of family to each other here in America.”

Though the family has a long road ahead, a volunteer tutor and the generosity of other donors and volunteers, are helping them slowly rebuild a sense of home and belonging. Though Yao and Abdul’s families come from different regions and language groups, their shared experiences allow them to celebrate and help each other. A relationship with Yao has also given Abdul’s family something important: the chance to extend hospitality and welcome in return. Though their circumstances are different, “as immigrants here, we share the various sides of it,” Yao says. “We go through some of the tough stuff and rejoice for some of the experiences that are great.”

World Relief’s volunteers get to build relationships that might not happen otherwise—but that can be truly life-changing. Even as someone from the same country, Yao admits, “Since they are from the north and I am from the south, it’s hard to say how our relationship would have looked if we were back in our country.” Yet by signing up to tutor an immigrant student, he gained the opportunity both to welcome Abdul and his family to their new home and to receive their gift of hospitality in return. Volunteering creates this opportunity: a chance to connect with those who are different and extend a warm welcome – oftentimes being surprised and learning from the hospitality you receive in return.

Thank you for walking with Abdul and his family and for bringing them together with Yao. Your generosity helps families rebuild their lives — volunteer or donate today to discover how you too can be transformed in the process.

Medina

Every day World Relief staff and volunteers are invited into stories. We are challenged to recognize the nuanced image of God in each person we serve, and remember that their stories stretch far beyond the boundaries of words like “immigrant, refugee, asylum-seeker.” The posts in this section—voiced in first-person, too long for social media, and lightly edited—extend that invitation to you.

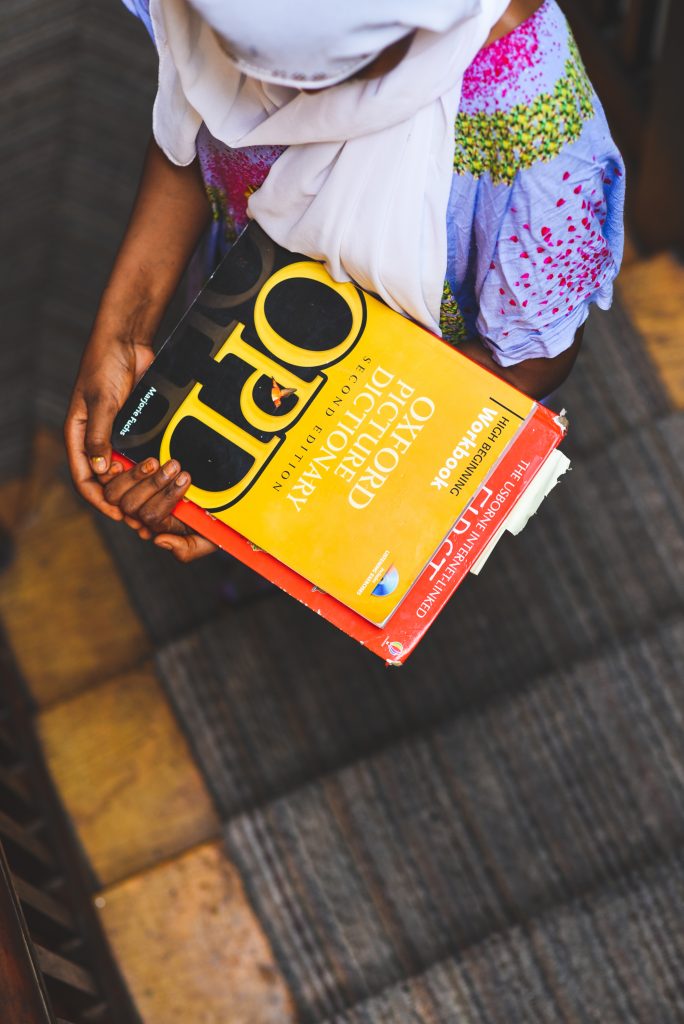

In this post we meet Medina. She’s 17, has learned four languages, and her dream is to be an English teacher. Her family is from the Afar people group of East Africa, and they were forcibly displaced from Eritrea to Ethiopia when Medina was a little girl. When she arrived in the U.S. in 2018, it was the second time she started learning a new country and new language.

Middle Child

Medina — In our country, they start from your own name, then your father, then your grandfather. For example, Fatuma Ali Hassan. But in America they just say Fatuma Hassan. My mom has a nickname. She was her father’s favorite child. So he used to call her Luli. The meaning of Luli – I don’t know how to say it in English – it’s something like a diamond, or gold. A lot of people used to call me Medi, but my nickname doesn’t have a meaning.

Before my little sister was born, my brothers used to listen to me and do whatever I wanted for me because I was the youngest one in our house. But after she was born, they did whatever she wanted for her. Now I’m in the middle so they don’t listen to me that much. Most of the time the middle one has to do everything. They say, “go and clean the room.” And if you say no, they pay you. They say, “I’m gonna give you ten bucks.”

America: “It’s good. It’s cold.”

When we came the U.S., it was me and my mom and my sister and my brother. My other brother and his family came before us. I think they came like one week before. We didn’t know we’d come that fast after my brother. But we were really happy when they said, “it’s time for you.” We had no idea what life in the U.S. would be like. We had some friends who moved here already, and they were telling us a little bit about America. They said, “It’s good. It’s cold.”

We were excited to see America – what it looks like and everything. For some people coming to the US takes like two years or three years. My other two brothers in Ethiopia are also waiting for their chance. One of them has a wife and one child.

When I went from Eretria to Ethiopia, it was a different life. And now it’s a different life in the USA. When I went to Ethiopia, I was seven or something. I don’t remember exactly. In Eritrea I used to speak Tigrinya, because that’s the language most of the people speak there. And when I came to Ethiopia, I completely forgot Tigrinya and I learned Amharic. Now in the U.S.A. I’m kind of forgetting some Amharic, and I’m learning English. In Amharic, when you write, it’s hard. Tigrinya uses the same letters as Amharic, I think. But in English, the letters are the same as the letters in Afar. My family speaks Afar, and I will never forget that language because we always speak it in the house and everywhere.

As a community of World Relief donors and volunteers, you have supported Medina and her family as they continue adapting in their journey from displacement to belonging. Through employment support, for example, you helped her brother increase his earning power by $10 per hour since his first job in the U.S.

Pizza & New Friends

I’m not gonna lie. School was very different over there in Ethiopia. I used to go sometimes and not go sometimes. It was half a day. We used to go in the morning and get out at lunch time. We all spoke the same language there, and we could say anything we wanted to each other. But here, sometimes if you want to say something to your friends, but you don‘t know how it is in English, it’s a little bit harder to explain.

I started in 9th grade in the U.S. in 2018. The first day of school was pretty hard. We didn’t know anyone. We didn’t know anything about English – just how to say “hello.” That was it. We didn’t eat the lunch. We didn’t like the food, or the milk. The first two days I brought my own food from home. But after a few days passed, I saw the pizza and I fell in love with it. There were some Muslim friends, and they told me the pizza was Halal. So it was okay to eat it. It’s really good.

After a while, we found friends. There were some girls who all came from Africa, but our language was not the same. They didn’t know English, and I didn’t know English. I think they’re from Tanzania. My English teacher helped a lot. She was so nice. She was understanding us, even though we didn’t speak English. Like when we explained to her with our hands if we needed water or something, she was understanding. My favorite subject is English. I’m bad at math. And I’m not that good at English actually, but when I try, it gets better.

You’ve been with Medina’s whole family through key moments like the first day of school in a new country. When COVID-19 hit, they had a team of volunteers who provided social connection, helped navigate shelter-in-place protocols, and offered emergency rental support when family members were laid off.

Dream Jobs

My tutor Jenny’s also really nice. I’ve only met her online. She lives in Indiana. She helps me with everything. We tell about ourselves. She tells me her story and I tell her my story. She told me about her family, and how she’s going to university. She’s from Korea, and lives with her mother and father and brother, and has some family in Korea. When I don‘t have homework we do extra stuff – reading and writing practice.

Jenny’s dream job is to be a doctor, and my dream job is to be an English teacher. English is not easy, but if you try and never give up it gets better and better. Other subjects are a little bit harder for me than English. So that’s why I feel like I want to be an English teacher. I think I‘ll teach kids, like 1st grade or second grade. (Read about Jenny’s path from interested to engaged here).

When I came to the US, I didn’t know how to speak English. A lot of people say I learn fast. That’s something I’m proud of. Another good thing is back in Ethiopia, to go somewhere for fun, it was a little bit far from my city. But here you can go downtown, to the zoo, to the beach. In the summer, Mr. Daniel from World Relief used to take us places. It was so fun, I’ll never forget. My favorite was the zoo. When we saw the animals and stuff like that. I hope the summer program can be in person this year.

Tik Tok & Covid

Learning on the computer is really hard. I go to Mather High School, and we are still not going in-person. The hardest part is sometimes the internet cuts off. Sometimes the computer is not working. Sometimes you just want to sleep. The teachers post the homework on google classroom and we send it back. It goes from 8am to 3:15pm. You get tired of sitting all day.

I feel like it’s way better to be in person. When everything is open. You can go everywhere without a mask. You can hang out and eat at restaurants. But now some people feel scared. Right now in our free time we just watch Youtube and movies. My little sister is on Tik Tok all day, doing a new dance, then a new dance. She makes her own videos, but I just watch. One time she made like 100 videos in a day. Tik Tok is crazy. If you watch Tik Tok, you forget about the other things.

Together, we’ve helped over 400,000 people like Medina and her family rebuild their lives in the United States. Continue your support today.

Photos by Rachel Wassink | Writing and interview by Jacob Mau

Rebuilding Connection and Pride

Every day World Relief staff and volunteers are invited into stories. We are challenged to recognize the nuanced image of God in each person we serve, and remember that their stories stretch far beyond the boundaries of words like “immigrant, refugee, asylum-seeker.” The posts in this section—voiced in first-person, too long for social media, and lightly edited—extend that invitation to you.

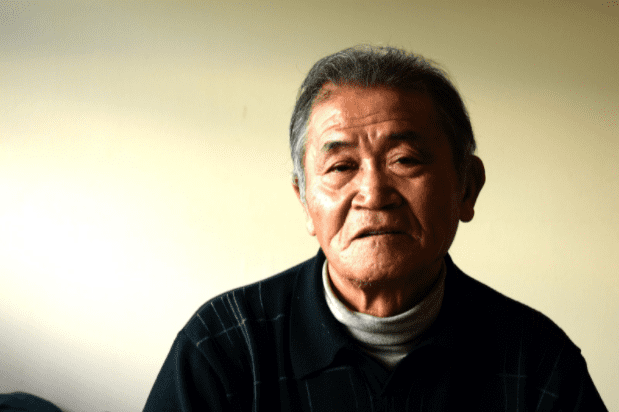

In this post we meet Gao Guanghua. When he arrived in the U.S. after spending years as a refugee in Thailand, you were there to walk alongside him. As a community of volunteers and donors, you helped Gao find a doctor who speaks his language, gain access to subsidized senior housing, and connect with Chinese-American friends.

Journey

My journey to America is a long story, but I can make it brief. In China, I was a doctor. I was a soldier. I was a teacher. In 1989, June 4, the Tiananmen Square event happened, as we all know. I went from my home to Tiananmen Square to participate. After that, I was affected in a negative way because of my participation. So eventually, I went to Thailand and I stayed there seven or eight years.

I had been a doctor in Chinese medicine for ten years. So, in Thailand I could make my personal information public and open my own clinic. I also worked at a hospital and split the profits with my supervisor. But now in the U.S., not only can I not open a clinic. I cannot even be a doctor. If I want to be a doctor, I must have my certificate mailed here from China. Then I have to take some tests and turn it into an American certificate in order to be a doctor legally here. In that sense, I had more freedom in Thailand than I have here. It’s like a hero who has no place to show off (laughs).

Anyway, UNHCR had an office in Bangkok. I spent a lot of money applying to become a refugee. It took a lot of time and it was complicated. Eventually, they approved me as an international refugee. It was a different kind of refugee than the way we talk about it in my culture. It doesn’t mean you have to be homeless. It’s more about people being politically persecuted. Most of the refugees from China are refugees because they are persecuted by the Chinese government. I belong to that group. So I was approved as a refuge, and after that UNHCR took care of me very carefully and sent me to the U.S. I came here, and got some benefits from the U.S. government.

My caseworker found a college student — also from China — who picked me up at the airport. All my I.D. and documents are now at World Relief. I didn’t have to get a lawyer or spend any money. WR just actively provided me with those things. This is a brief summary of how I came to the U.S.

A Story from My Childhood

I have so many stories from my life, I don’t know where to start. Here’s a positive story from when I was in middle school – around 15 years old. There were six middle schools around several kilometers from my home to the north, and that’s where I went to school. I had to go across a river to get to school. It was around 5-6 meters wide. In winter we could just walk on the ice. In summer, usually the water was not that strong. It only came up to our chests, and we could just walk across. But in the rainy season – July and August – it’s stormy. Then, people will sink into the water if they cannot swim.

During one rainy season, there were 8 or 10 times when the flowing of the water was harsh. Me and five other boys needed to cross the river. There was no boat, and I was the only one who knew how to swim. So I brought them across the river one-by-one.

We all brought lunches to school. We called it dry food. Life wasn’t easy, so we ate these wild vegetables and a kind of wild wheat. We made it into a kind of steamed bun. So everybody carried many of these buns. I took my friends across the river. They had to take off their clothes becuase if they wore them into the water, it was hard for me to take them swimming. After I got them all across, I came back to get all the food too. I was so tired. The boys gave me applause.

When I got to school, my teacher praised me too. And the president also honored me in front of all the students. They even put me into the school newspaper. I was so proud of myself because of this. This was in the 1960’s. I didn’t have a cell phone to take a picture of that newspaper article so I could remember it. We didn’t even have bicycles. We just walked to school.

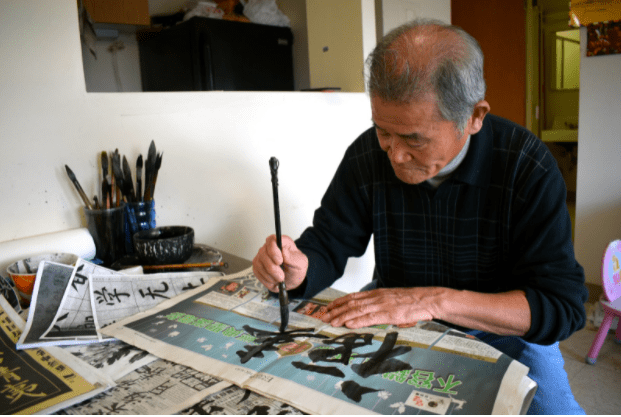

Teaching School and Calligraphy

When I was a student, it was before Chairman Mao’s cultural revolution. Later, I became a middle school teacher after the cultural revolution. Before the cultural revolution, most teachers were not officially hired. But I was officially hired in a public school.

I taught in schools in remote areas of the countryside. Physics, chemistry, math, geography, biology, and some other courses like writing, music, physical education, and arts. Calligraphy was not an important part of what we taught.

If you went to school before the cultural revolution, you’d learn calligraphy. If you went after, you wouldn’t learn calligraphy. It disappeared. So right now, very few people in China can write like this.

Calligraphy is a treasure of Chinese culture. I was seven or eight years old when I started learning calligraphy. I didn’t like it at the beginning. But the more I practiced, the more I developed an interest. Especially in my home town in the northern part of China, people in my father’s generation could do excellent calligraphy. Each year for the Chinese new year, every home had a person who could create a banner for each side of the door. The banners had phrases or blessings with the same general idea – well wishes for people in their careers, wishes that they’d be prosperous, peaceful, and healthy. But there are a variety of ways to say it.

Now, I’m part of Chinese calligraphy organization here in Chicago. We do a lesson once a week. We’ll give you one brush and some ink for free. It used to be $10 per lesson, but now it’s only $5. Still, very few people come to learn. There’s another organization that does lessons for free, so there are more people there. Most of them are elderly Chinese. Also, every Tuesday, I go to a senior center in little Vietnam and teach Chinese calligraphy.

Explaining a Chinese Proverb

This one is a saying from Confucius, quoted by another very famous leader. In Chinese, each character represents an idea. So, this first one on the right means the heavens. The second one means everything under heaven – many people, many nations, but they’re all human beings. The third one has many different meanings. But in this context it means to do something in order to reach a goal. The last one represents the public. Look at the image of this last character. One stroke to the left, one stroke to the right. Below those two strokes is a symbol that means, “self.” It basically means, eight people can make a group or fellowship.

So the combined meaning of the whole phrase is: Everything under the heaven and down to the earth is done for the public. For ordinary people. It’s not determined by only one person or politician.

We can use this to describe America’s political system. But China is far away from that kind of system. And that’s the best I can explain it. The Chinese language is very deep. Very complicated. For example, maybe you can learn English in three years, but you cannot acquire Chinese in thirty years.

Like his language, Gao Guanghua’s story is deep and rich. Together, we’ve helped restore a tiny bit of the pride and connection he felt back when he had his own medical practice, or the day he swam his classmates across the river. You can help more people like Gao rebuild their lives in the U.S.