Staff Reflections

The Good News Report

“We are all going through an incredibly trying time. But through all the anxiety, through all the confusion, through all the isolation, through all the Tiger King, somehow the human spirit found a way to break through and blow us all away.”

— John Krasinksi

The world is crumbling… or so it would seem. Everywhere we look stories of viruses, job loss and economic collapse fill our newsfeeds. In such a time as this, it would be easy to draw back in fear, to collapse under the weight of the unknown. But we’ve been wondering — might there be a better way to cope with our collective grief? We think so!

Enter: The Good News Report!

Every day, we receive stories from our local offices and church partners around the world — stories of people, just like you, who are sharing love and spreading hope right within their own communities. Whether it’s apartment dwellers in Atlanta cheering on healthcare workers from their balconies, or a World Relief volunteer in Dupage donating a much-needed wheelchair to an asylum seeker, these stories from our World Relief family and beyond are inspiring. They’re uplifting! They’re a breath of fresh air in the middle of much unknown.

While there is still much to mourn and a lot of change and uncertainty to walk through, these stories have brought us some much-needed refreshment, and we thought you might need the refreshment as well.

With that in mind, we are committed to sharing good news from our offices and communities for the next several weeks. We hope these stories are a welcomed break from the heavy and the hard. We hope they give you strength as you move through your day. We hope they lift your eyes and fill your spirits as you discover that love still remains, even in the midst of crisis.

Westwood Community Church – Excelsior, MN

One of the best things we’re seeing come out of this crisis is the creativity springing up out of local churches as they find new ways to connect with their communities and serve others.

In Excelsior, MN, World Relief church partner Westwood Community Church had no problem shifting their services to an online experience. They had been LiveStreaming their services for several years and had recently implemented an online campus service just six months earlier.

In the midst of the transition, they reached out to one of their immigrant church partners, Destino Covenant Church in Minneapolis, to see if there was anything they needed. Destino’s lead pastor, Mauricio Dell, expressed a need to create a video so his church could put their Sunday services online. Westwood sprung into action, and days later, members of the Westwood Communications team met Mauricio and his wife, Jacquelyn, to film the service. Mauricio preached in Spanish while Jacquelyn translated in English. The video was uploaded and ready to stream the following Sunday.

But perhaps the best part of the story is that Mauricio and Jacquelyn were able to learn how to video the service themselves. The Westwood Communications team showed them what type of lighting to use and how to properly upload the videos. Now, Mauricio and Jacquelyn are taping their own services and no longer need to travel 30 miles to Westwood to get the job done.

The Spokane Chinese Association: Spokane, WA

Washington State has been one of the states hardest hit by the Coronavirus. Our World Relief Spokane team has been hard work making adjustments and meeting needs even as they social distance. Last week, they shared a story from within the Spokane community that encouraged them and us!

The Spokane Chinese Association first became aware of the novel Coronavirus as it was spreading across Wuhan. When the virus hit their own community in Spokane, they wanted to help. Led by their president, Ping Ping, the association was able to distribute more than 600 masks to people throughout the community. But Ping wanted to do more!

She began collecting donations and was able to donate 400 masks to the Spokane Police Department, a gift the police captain said was much needed. Now, Ping has raised more than $6,000 that she plans to use to donate more masks to first responders and medical workers in the Spokane area.

You can read more of Ping’s story here.

Rachel Clair serves as a Content Writer at World Relief. With a background in creative writing and children’s ministry, she is passionate about helping people of all ages think creatively and love God with their hearts, souls and minds.

Grief and Hope: A Rwandan Story

History

Today marks the 26th Commemoration of the 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi, a grim moment in my country’s history and one that I remember vividly.

I grew up in Rusizi District on the western side of Rwanda. The genocide was carried out in my home village the same way it was throughout the rest of the country. Although communication technology was not as advanced as it is today, information was still able to spread, proof that the genocide was well planned.

In Rwanda, the post-independence period (1962-1994) was run under divisive and discriminatory ideology, where the successive regimes considered some of its citizens as foreigners, enemies and moles in the open. Most of these citizens were denied education, jobs and other rights including trading licenses and driving permits, to name a few. This discriminatory ideology culminated in the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi, killing a large number of people in a just few days (about 1,070,014 Tutsi killed in only 100 days). The genocide left behind around 300,000 orphans and non-accompanied minors, about 500,000 widows and over 3,000,000 refugees.

My home was completely destroyed during the genocide, and the people I lived with had been killed. By God’s protection, I survived and left my village at the end of April. In September, I was blessed to get to travel to Kigali, which was the secured area at the time. I joined my uncles who had just returned from another country.

Grief in the Aftermath

The aftermath of the genocide was horrible. Everywhere I looked dead bodies lay in the streets. Dogs roamed around, becoming aggressive as they got used to feeding on the bodies. Most of the homes had been destroyed. Hospitals were filled with wounded people, but had very few supplies and almost no personnel to care for the wounded. There was no security. Widows and orphans were desperate. Hopelessness pervaded every corner of the city.

Survivors were very scared. They had lost everything. They were traumatized, and their trust in others was gone. They felt that no one could understand their sorrow, which was true. The few people who were out walking around cried in deep grief as they retold stories of how their loved ones were brutally killed. It seemed impossible that peace would ever exist again. No one could imagine that the city would ever be rebuilt.

I, too, felt little hope. I was ready to die, actually. My prayer was to die soon because I didn’t have any hope of living when I looked at the circumstances around me. I couldn’t expect that life would ever have meaning or flavor or that the country would ever have peace again. I was full of tears as the horrifying memories of noise and sounds of both perpetrators and victims were buried in my heart.

It was difficult for me to return to school. I didn’t have any reason to go back because life was pointless in my mind. The only thing that kept me going and convinced me to go back to school was my faith. I kept reminding myself that God loved me and trusting that, even though I didn’t feel it at the time, he was a Provider and Healer. I prayed often and read my Bible, clinging to the words in John 3:16— For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only son that whosoever believes in him will not perish, but have eternal life.

Rebuilding Peace

During the 100 days of genocide, our country felt abandoned by the outside world. There was no global response. After the genocide, though, we began seeing NGO’s and other stakeholders come to help with food, medical supplies, blankets, rehabilitation services and more.

The soldiers who had liberated the country walked the streets saying, “Humura,” which means “don’t worry”, to everyone they saw. They were kind and supportive. Their words were comforting and powerful in restoring peace of mind and building trust and hope.

World Relief arrived shortly after the genocide to provide humanitarian support as well. They brought food, clothing, shelter, medical supplies and counseling to all who were affected. In addition to meeting these basic needs, it was clear that a long road lay ahead for rebuilding peace and finding reconciliation. As Rwandans, we’d need to confront all forms of discrimination and exclusion. Unity and reconciliation was the only option for our country to emerge from its divided past.

We’d need to redefine the Rwandan identity, replacing the ethnic identities of the past with a shared sense of Rwandanness. We’d need to rebuild trust in our leaders and create a culture of responsiveness, transparency and accountability across the public and private sectors. And we’d need to establish equitable and inclusive policies that addressed issues on gender, disability, poverty alleviation, education and public service.

It has been 26 years since the genocide took place, and I am proud to say Rwanda is a completely different place than it was back then. It was not easy to get people to believe that unity and reconciliation would be possible after the genocide, but we have proven it is possible if concerned people own the process and commit to changing their thoughts and behaviors.

I have watched as our nation and our people have owned the healing process and committed to whatever was necessary to see it through. We’ve accepted and acknowledged what happened. We’ve set goals and thought often of all the reasons peace and reconciliation were worth fighting for. We’ve monitored our progress, acknowledged failure and learned from it. We have worked hard and forgiven often, and we have celebrated every victory and achievement.

Hope for Today

Rwanda today is so different from Rwanda in 1994. Development and education has improved. Investment in youth and capacity building initiatives have grown. Women have been lifted up and their contributions to the development of the country have been highly noticed. The government has been highly committed in bringing peace, establishing clear policies and monitoring compliance as much as possible.

My hope is that other countries would learn from Rwanda because no one benefits from cultural or ethnic conflict in the short-term or long-term. The wounds from cultural conflict can last for years, and are felt by all. Prevention is much better than having to go through a healing process so I pray that other countries would be proactive and implement strong investments in current conflict resolution strategies.

I am grateful for the healing Rwanda has experienced. I am grateful for the healing I have experienced. I can testify that God is Protector, Provider, Healer and that he can restore life to everyone and every nation. Even now, as I know so many are struggling with fear and uncertainty with the global COVID-19 crisis, my encouragement is to trust God even during the impossible. There is no season, no virus, no situation that He cannot change from dark to bright. God is Faithful.

Jacqueline Mukashema is the Director of Administration and Finance, World Relief Rwanda. She began working for World Relief in 2006 as a Chief Accountant and has served faithfully in various finance and administration roles. She studied accounting up to the Masters level and loves this field. She is a born again, committed Christian and is passionate about serving the vulnerable— especially orphans. In her free time she likes quality time with her family and cooking. She’s married to her husband, Jean de Dieu, and they are blessed with five children— Esther, Etienne, Ruth, Honnete and Asher.

Scarcity, Immigration and Having Enough

In the human world, abundance does not happen automatically. It is created when we have the sense to choose community, to come together to celebrate and share our common store.

– Parker Palmer, Let Your Life Speak

Seven Years of Waiting

Arooj leans back against the refrigerator in her dimly lit kitchen, her head resting heavily atop postcards and family photos. She holds a brightly lit cell phone out in front of her.

“Yeah, but they never informed me clearly of what clearance they need,” her husband Sunny’s voice is heard from the speaker. “They are only sending me the emails — we are waiting for some clearance from the U.S., please wait… So I am living here alone, you are living there alone.”

Arooj closes her eyes, breathing deeply before she speaks.

“Yeah. Just keep praying…Be strong. Be faithful. Everything will be alright.”

Arooj and Sunny fled their home in Pakistan in 2013 when Muslim extremists threatened to kill them and their families. Arooj made it to Sri Lanka, but Sunny was caught and kept from joining her. While Arooj was resettled in the United States in 2017, her husband’s resettlement has yet to be approved. The couple has only been physically together for six months out of the last seven years. Now they’re waiting — waiting on a process that seems ever-changing and ever more difficult to complete.

A Culture of Scarcity

The United States has historically been a place of refuge for people fleeing violence and persecution, but drastic changes in immigration and refugee resettlement policies have left many, like Sunny, in a state of limbo. At its best, the U.S. has been known as a place of hope and opportunity, where dreams can come true regardless of race, socioeconomic, ethnic or cultural background. Recently, however, our national rhetoric has shifted. Phrases like, ‘we’re full,’ ‘there’s no room for you,’ ‘you’ll drain our resources,’ and ‘we don’t have enough’ have replaced a culture of compassion and unearthed a deeply seated culture of scarcity.

In 2012, author and researcher, Brene Brown published a book titled, Daring Greatly. In it, she discusses a cultural shift she’s noticed in the United States over the last several years:

“The world has never been an easy place,” she writes, “but the past decade has been traumatic for so many people… From 9/11, multiple wars, and the recession to catastrophic natural disasters and the increase in random violence and school shootings, [we’ve survived] events that have torn at our sense of safety with such force that we’ve experienced trauma…

“Worrying about scarcity is our culture’s version of post-traumatic stress. It happens when we’ve been through too much, and rather than coming together to heal (which requires vulnerability), we’re angry and scared and at each other’s throats.”

That description is eerily accurate of our current culture.

If you’re like me, you struggle with scarcity almost daily. You wake up thinking there’s not enough time to get everything done, not enough resources to get what you want, not enough know-how to accomplish your goals… simply, not enough. But if scarcity and this pervading belief that you don’t have enough — that we don’t have enough — is driving the policies we support and the rhetoric we use, then what does that say about the God we serve?

God’s Promise to Us

All throughout scripture, God promises to provide for our every need. He says to look at the birds of the air and how he feeds them. Are we not much more valuable than they? He also promises to keep us safe, to be our place of refuge and to shelter us beneath his wings. And at the same time, he calls us to be compassionate — to care for the vulnerable and welcome the foreigner among us. We take this call seriously at World Relief and consider it an essential task for followers of Jesus.

At World Relief, we do not advocate for open borders. But we do advocate for policies that are both compassionate and secure. These ideals need not be mutually exclusive. We also advocate and call for a church — God’s people — to be a voice of compassion and to trust God when he says that he is enough and he will provide enough.

Perhaps you’ve heard it said that anytime there are gaps in our knowledge, fear fills those gaps. If we’re fearfully believing that immigrants and other refugees are draining our system and we don’t have enough, could it be that we just don’t know enough about the facts?

The Facts

In 2016, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services issued a report that revealed between 2005 and 2014, refugees and asylees contributed $63 billion more in government revenue than they used in public services. These findings, however, were largely ignored. A fact sheet was released later that year detailing all the ways refugees spent public money without providing any of the details about how much they contribute.

What’s more, according to the National Immigration Forum, immigrants are twice as likely to start new businesses than U.S.-born citizens. Immigrants have founded more than 51% of the country’s new start-up businesses, and in 2016, these companies employed an average of 760 people.

Immigrants and refugees like Arooj are grateful for the refuge America has provided for them and are eager to rebuild their lives and contribute to our economy and our culture.

“We have a big plan, actually…” Arooj says smiling, “that whenever we have kids, one of our kids is going to go to U.S. Army… that’s what we believe!”

A Call to Trust

Author Parker Palmer once wrote that “whether the scarce resource is money or love or power or words, the true law of life is that we generate more of whatever seems scarce by trusting its supply and passing it around.”

As we move forward, let’s be conscious of the ways our internal stories and misinformation might be shaping our national narrative and choose to generate knowledge, trust and truth rather than letting scarcity and fear win out.

Learn more about Arooj and Sunny’s story.

This story is taken from “They Are Us,” a video produced by Jordan Halland.

Rachel Clair serves as a Content Writer at World Relief. With a background in creative writing and children’s ministry, she is passionate about helping people of all ages think creatively and love God with their hearts, souls and minds.

Here to Stay

A little over a week ago, we received some very sad news. Texas Governor Greg Abbott sent a letter to the federal government announcing that he would halt all future refugee resettlement to the state of Texas – an authority given to states in a recent executive order.

That decision has been a huge disappointment to the hundreds of people seeking refuge in our country.

Texas has historically been a leader in welcoming refugees to the United States, resettling over 60,000 in the last decade, more than any other single state. As a Texan, I know that these resilient women, men and children have become an integral part of the Lone Star State, contributing significantly to our state’s economic growth and becoming beloved parts of our churches, schools and communities.

In his letter, Governor Abbott implied that refugees are a burden. Our forty years of experience working with refugees in Texas has proven that, far from that, they are a blessing to the communities that welcome them.

Many of these refugees-turned-Texans have loved ones abroad who are waiting for approval to resettle in the U.S. World Relief has been reuniting families like these who have been torn apart by violence and oppression for decades. The moment a father sees his children for the first time in several years is a moment that leaves you speechless. It is a moment that illustrates so much of our call as Christians to welcome the stranger. That moment should not be banned in Texas.

Similarly, thousands of the refugees welcomed in Texas over the past decade have been persecuted Christians — families who have fled their homes simply because of the very faith we share with them. At World Relief, we’ve had the privilege of joining with local churches to welcome these brothers and sisters in Christ, trusting Jesus’ words in Matthew 25, that in doing so, we are actually welcoming Him.

Over the past week, we have received calls from volunteers, donors, concerned Texans and churches who love and welcome refugees as part of their core ministry. They’ve asked us what this means for the refugees and immigrants they love and for our office.

We have one answer: Refugees and other vulnerable immigrants are here to stay, and so are we. God has called us to welcome and serve the most vulnerable, and so we continue.

Like you, we are deeply saddened when our leaders choose to turn away from the most vulnerable among us. Nevertheless, we are determined to continue helping you answer God’s call. Immigrants will continue to come to Texas. Thousands of refugees are already part of our communities, and they still need us.

At World Relief, your donations will provide refugees and other vulnerable immigrants with the vital services they need to start their new life. Your voice will help us continue to build welcoming communities in Texas. Your volunteer hours and our church partners will continue to bring people together to create lasting change in the lives of refugees and immigrants.

We celebrated last week when the Federal Court System issued an injunction against the Executive Order that allowed Governor Abbott to restrict the Church’s ability to welcome refugees. That ruling, however, isn’t permanent. While we know the future can seem uncertain, we will not ignore our calling. Together, we will stand with the vulnerable in Texas no matter what.

Troy Greisen is the director of World Relief Fort Worth.

I Survived the Vietnam War to Become a Proud American

I was born in Southern Vietnam in 1953. I grew up just like any other boy in my country and had a happy childhood.

Then news about war in Vietnam gradually appeared on the front pages of newspapers in the 1960’s, and things began to change

Like many young men in wartime, I reported for military service in South Vietnam at just 18 years of age. I learned we’d be fighting alongside our American allies, which filled many of us with hope. Little did we know, however, that the war in Vietnam would carry on for 19 years and four months. It finally ended in April of 1975, and I was sent to prison for a year for fighting on the South Vietnam side. Afterward, I was told to relocate to a wild area of the jungle called the “New Economic Zone.” Instead, I went to my mother’s hometown in the countryside and made my living as a farmer.

As a former South Vietnamese soldier, I knew I couldn’t stay in the country. My children would not be allowed to pass high school education. They would be barred from being successful people in society. But escape was difficult, very difficult. People who were caught trying to escape would serve long prison terms. After several failed attempts at escaping by myself, I paid a local fisherman to smuggle me out in his boat. Two days after we left, the boat’s engine failed, and a navy ship from Malaysia rescued us.

I was placed in a refugee camp in Malaysia, where I volunteered to work as part of the camp government. It was there I learned that because of my background, I would be resettled as a refugee in the West. As part of the U.S. refugee process, I was sent to the Philippines, where I learned that my future life would be in the U.S.

I finally entered America for the first time in August of 1989 and was welcomed by volunteers from a local church community. They gave me a room to live in and assisted me in acclimating to life in a strange new country.

At first, I was intimidated. Life was fast-paced, and there was a lot to get used to. For instance, coming from a tropical country, I was terrified of the cold. I didn’t have a TV so I never knew the weather report for the day. I would stick my hand out the window in the morning to see what it felt like so I knew what to wear. When winter came, I made the mistake of washing my winter coat and then hanging it outdoors to dry. When I brought it in at the end of the day, it had frozen to ice.

I was also mistrustful of Christians when I first arrived in America. To my knowledge, the Vietnamese kings did not like Christianity when it first spread to Vietnam. In the late 19th century, the French army came to “protect” new Vietnamese Christians from persecution, which eventually led to the French colonization of my country, and that lasted for almost a hundred years. Growing up a Buddhist, I was naturally suspicious of Christians.

But then I came to America, and people who didn’t share my religion or language – people who had nothing in common with me – went out of their way to help me.

They helped me simply because they cared about me, a stranger, and that caused something to change in me. I wanted to know what this religion was that inspired people to care for me like that so I began attending church. Eventually I, too, became a Christian.

Today, I am a leader in my church. I am also a father and grandfather. My son became a U.S. Marine and is now a junior pastor. I work as a social worker for World Relief, helping other refugees adjust to life in the U.S. I feel blessed to be able to do this work. I understand that many refugees have survived harrowing ordeals and are skeptical of receiving help at first. I use my experience to help them regain their trust in people. I love the work I do.

My brother and sister also became U.S. citizens, but my 94-year-old mother still lives in Vietnam. In 30 years, I have only been able to visit her there four times. My heart aches from missing my mother, but I still don’t feel safe going back there.

When I was in prison in Vietnam, defeated and suffering, I never imagined I could have this kind of life. I want Americans to know how truly blessed they are. Here, we pursue the ideals of freedom and equality. In this country, the poor and the rich shop side-by-side at Walmart. No one is above the law. If people disagree with the government, they can voice their opinions and not be afraid of retaliation.

This is the United States I love and am proud to belong to. I appreciate the opportunity to live in freedom. I hope that by coming together, embracing the American ideals of freedom and equality, and shouldering our societal responsibilities, we can assure the American public refugees and other immigrants are worth welcoming.

Some people say what I endured as a young man, and my experience as a refugee, is remarkable. But I disagree. Living in this country – a country where people are willing to step forward and help strangers simply because it is good and right – that is the remarkable thing.

Chau Ly is a former refugee and social worker at World Relief.

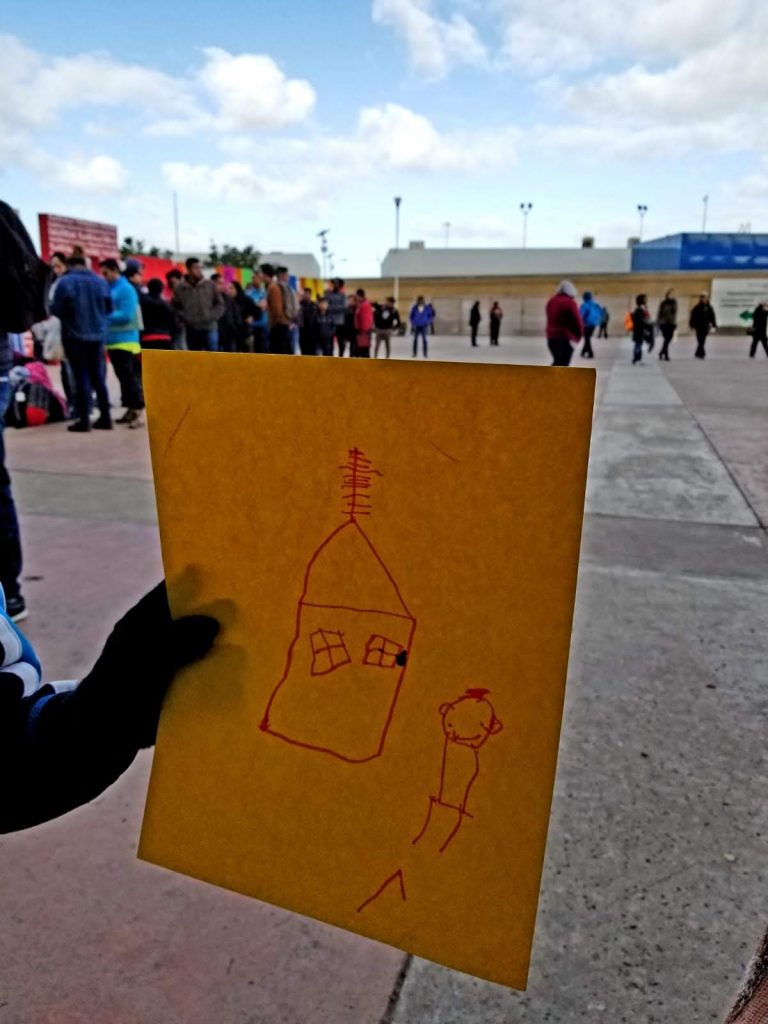

Take a Number

People around the world are fleeing violence, oppression and poverty. I visited Tijuana in early October to get a firsthand look at what asylum seekers experience when they reach our border.

U.S. asylum law states that any individual arriving in the United States is allowed to request asylum, whether or not they have arrived at a designated port of arrival. Anyone wishing to claim asylum has historically been referred to an asylum officer who could then process their claim.

In 2018, however, things changed. The government instituted an informal immigration process known as metering. Under this metering process, rather than hearing the claims of asylees who arrive at the U.S. border, Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) agents are stopping families and individuals at the border, assigning them a number and returning them to Mexico to wait until their number is called. Once their number is called, only then can they claim asylum and begin the immigration court process. Hundreds of immigrants and asylees wait months in Mexico, with no way to know when their number will be called or if their request will be approved.

CBP claims this unofficial policy was put in place to assist with the backlog of asylum claims. However, fewer claims have been processed since metering was enacted and there has been little effort to hire more claims officers. This has left me to wonder whether the process was actually put in place to help, or to deter vulnerable people from seeking the protection they so desperately need. It’s also made me wonder, “Is stopping an asylum seeker before they cross the border to make their claim even legal? Moreover, is it a violation of human rights, US immigration and international law?”

Like those waiting to seek asylum, my morning in Tijuana started early. Each day, asylum seekers gather near the border in hopes that their number will be one of the few called that day. Those who are called will finally have a chance to formally claim asylum. On this particular day, only eight numbers were called. On World Refugee Day this past summer, not a single number was called.

I arrived at 8 a.m., just as the metering process was beginning. I waited just beyond the huddle of asylum seekers and met a young man whom World Relief was representing in his asylum claim. As a university student in Venezuela, this young man had joined a group of protestors who were demonstrating against the Maduro regime. As a result, he was followed by Maduro’s men, attacked and beaten for speaking out. Sadly, this is a common story in places like Venezuela.

Fearing for his life, my new friend fled Venezuela and arrived at a legal port of entry in Tijuana in May 2019. He took his metered number and returned to Mexico to begin his wait. Two months later, however, the US government changed course and decided that anyone who had passed through another country on their way to the U.S. needed to first claim asylum in that country, before claiming it in the U.S.

Although my new friend had arrived in the U.S. before this rule was put in place, he couldn’t officially claim asylum until his number was called. Had he not been stopped at the border and forced into the metering system, he could have claimed asylum as soon as he crossed into U.S. territory. What may feel like a technicality to you and me, could drastically alter this young man’s future. It’s highly likely his claim will not be granted because he did not seek asylum in any of the countries through which he had passed. My friend had followed the rules. He had taken a number, and now he’d likely be told to go back home.

In the midst of my sadness and frustration, I visited a small Baptist church on the Mexican side of the U.S./Mexico border and found some glimmer of hope. This small church had become a safe haven for many of the brave individuals and families who have traveled to the U.S. seeking asylum. On a typical Sunday, this congregation of only a 100 people or so, shelters up to 40 asylum seekers, whom they call “guests” rather than “immigrants.”

This church had taken spaces that they likely needed for their Sunday morning programming and turned them into dorm rooms. I walked through the church and saw the most beautiful wooden bunk beds I had ever seen! They may not have been much, but they were a sign of the local church in action.

This church had become God’s grace to people in need. While I found myself so saddened by the stories of asylum seekers and frustrated by the “take a number and then go back” procedures, I left feeling a sense of hope after seeing a clear picture of what God’s people, his church, could be.

Mark Lamb previously served as the Partnership Director at World Relief .

Voices From the Field: DR Congo

Yesterday was International Day to End Obstetric Fistula, a serious injury that can occur from complications in childbirth. The World Health Organization used this day to call on the international community to significantly raise awareness and intensify actions towards ending obstetric fistula.

An estimated 2 million women in sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, the Arab region, and Latin America and the Caribbean are living with this injury, and some 50,000 to 100,000 new cases develop each year. Yet fistula is almost entirely preventable. 1 Its persistence is a sign that more can be done.

We took a moment to talk with Dr. Esperance Ngondo*, staff in DR Congo, about this injury and our work in DR Congo to treat and prevent fistula.

What is fistula?

Obstetric and traumatic fistula presents as a hole between the tissues of the vaginal canal and bladder, vaginal canal and rectum or all three.

What causes Fistula?

We see fistula caused by a number of circumstances. Obstetric fistula occurs when girls whose bodies aren’t yet fully developed try to give birth. Young girls under the age of 16 are at greatest risk of developing obstetric fistula. Traumatic fistula, however, is typically the result of a violent rape. In the Congo, where rape is frequently used as a weapon of war, we focus most of our work on this type of traumatic fistula.

How did World Relief DRC begin working with women with this injury?

For more than ten years, the World Relief DR Congo office has been active in humanitarian programs and in projects promoting health, agriculture, microfinance, peace & conflict resolution, savings and institution building among churches and communities, 82% of our beneficiaries are women and children – the most vulnerable demographic across the board, but especially in Congo. As World Relief DR Congo implemented its numerous programs in the rural areas, it has been increasingly clear that sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) against women and young girls (ages 2 to 60) must be addressed.

What are the effects of fistula for a women in DR Congo?

When fistula occurs and is not treated, many women become incontinent and are often cast out by their families as shameful and dirty. Not only do women experience horrible physical effects of fistula, but there are painful social and emotional effects as well. In Congo, women who are raped face terrible rejection and stigmatization. If a woman is married, not only her own family, but her husband and husband’s family cast her out of the home leaving her feeling rejected and humiliated. Oftentimes these women become homeless. In fact, many of our volunteers find these women living hopeless and alone in the forest.

What programs does World Relief DRC offer to support women suffering from fistula?

World Relief has implemented a number of programs to provide medical, psychosocial and economic support to women who are survivors of sexual violence as well as women who have developed obstetric fistula. In partnership with a local hospital women receive treatment, often surgery, for fistula. After the initial surgery, programs are in place to support women; Income generating programs are offered to women to restore their dignity, as well as provide them with the opportunity for economic independence.

How successful are the programs?

In general, fistula repair surgery has an average 80% success, but for World Relief and our partner hospital, we see a 95% success rate. We see God blessing our work again and again. Desperate and hopeless women are finding hope and experiencing a renewed sense of self-worth and dignity.

1. World Health Organization. Retrieved May 23, 2019 from https://www.who.int/life-course/news/events/intl-day-to-end-obstetric-fistula/en/.

*Dr. Esperance Ngondo is a World Relief DRC’s Sexual and Gender Based Violence (SGBV) & HIV/AIDS Health Officer. After completing her degree in medicine from the University of Goma, DRC in 2013 she worked at Bethesda Baptist Hospital in Goma in a program supported by Doctors without Borders, specializing in diagnosing and treating cases of SGBV. She began working as WR’s SGBV-HIV/AIDS Health Officer in 2015. Dr. Ngondo and her husband, Innocent, have three young daughters.

Dana North serves as the Marketing Manager at World Relief. With a background in graphic design and advertising and experiences in community development and transformation, Dana seeks to use the power of words and action to help create a better world. Dana is especially passionate about seeking justice for women and girls around the world.

Home Is Where Your Heart Is

In celebration of International Day of Families, we honor and recognize the hundreds of church leaders, volunteers and staff that sacrificially give their time and energy to our Families for Life program and, more importantly, to the men, women and children whose lives have been changed through the volunteers’, leaders’ and staff’s love in action.

Home

A place to go. People who love you. Somewhere you belong. A place to settle down. Home defines place, family, belonging. Identity and compassion.

Regardless of country—Papua, Indonesia, India, Malawi or Democratic Republic of Congo, home is often defined in these similar ways. In fact, it’s likely how you define it as well.

And yet, for many, the ideals associated with ‘home’, and their dreams for family, are a far cry from the reality. Instead, they grapple with broken marriages and relationships, gender injustice, arguments over resources and decision making, difficulty communicating with their children—the list is long and weighty.

But thanks to your support, couples around the world are experiencing renewed hope in their marriages and families through a program we call Families for Life (FFL) program.

Biblical Marriage

Partners like you have helped couples to grow and flourish together as God’s Word describes through FFL programs that restore relationships between husbands and wives to their fullest potential and recalibrate thinking around family and marriage.

In FFL, couples are invited to a workshop to explore biblical and cultural components of marriage. There, they learn that one entire book of the Bible is devoted to the theme of love and marriage—the Song of Songs—a book that is marked with metaphors of love and filled with messages of friendship, attraction, fulfillment and commitment.

After studying Song of Songs, husbands and wives discuss together what it means to be forever friends and intimate companions. They discuss what husbands and wives bring to their homes, and more importantly, to each other, and come to recognize the critical importance of nurturing and loving one another as a couple. Your generosity is radically shifting mindsets for many couples as they discover that a spouse can and should be someone you trust, spend time with, enjoy, confide in, talk to about anything and for whom you willingly sacrifice.

Behavioral Change Curriculum

Layered atop of this biblical study, Families for Life integrates a culturally relevant, story-based curriculum that addresses misbeliefs about women, the importance of valuing and respecting one another, gender equality and biblical sex in marriage. The curriculum is designed to address critical issues among couples and raise questions for reflection and opportunities for change.

As couples’ beliefs around marriage and family shift, so too, do behaviors. Reductions in gender-based violence, alcohol abuse, poverty and unfaithfulness become apparent. Husbands begin to include their wives in decision making processes, wives learn they, too, can contribute to their families resources through income-generating activitIes, parents come to realize the value of educating their children, both girls and boys, and families begin to diligently and intentionally plan for their futures. As perspectives change and mindset shifts occur, deep-seated conflicts are tackled, harmful traditions are questioned and children and generations to come are impacted.

Sustainable Impact

Beyond the powerful restoration of relationships and the resulting behavior-changes that occur, FFL lays the groundwork inside the home for our other programs to have a truly sustainable impact. When we acknowledge the centrality of the family unit in dictating and defining identity, beliefs and behaviors, we tap into the most effective way of impacting sustainable change across a multitude of areas—physical, social, emotional and spiritual. By ensuring both man and woman, boy and girl, are equally valued, given equal opportunity and are equally empowered, the impact of our programming is magnified tenfold.

A Beautiful Vision

God has illustrated to us what He intends for marriage—unity and harmony in diversity and oneness. Marriage should be a sacred reflection of this fullness of life as God designed. Yet, every culture and every marriage fails to reach this standard. The goal of Families for Life is to reach homes and churches with critical lessons that reveal God’s beautiful vision for marriage, and leave behind tools, training and structures for churches to extend these messages for multiplied impact.

Thanks to your support, we’ve completed six country-specific curriculums and trained over 25,000 couples through churches, savings groups and community gatherings in Indonesia, India, Burundi, DRC, Malawi and Haiti. The program is rapidly growing, with plans to expand in the next year to Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Cambodia and eventually Sudan.

Home is, indeed, where our hearts are. It is where mutual honor and support, care and commitment and physical attraction between wives and husbands should grow in every corner of our world.

“I used to drink and spend all our money when I was paid after work. Now, after being in an FFL workshop, I come straight home to my wife and give it to her to spend for the needs of our family. We decide what to do together.” – Husband, Burundi

“In our village, we are seeing less and less violence. People are not coming to me to intervene in cases of violence against women because of this program.” Village chief, Malawi

“I want to tell you, my wife, that I have not honored you as I should. I am sorry. Will you forgive me?” – Pastor Semiti, Democratic Republic of Congo

Deborah Dortzbach is the Senior Program Advisor for World Relief. She has been involved in church-based HIV/AIDS prevention and care since the early 1990s. Prior to joining World Relief she directed MAP International’s HIV/AIDS programs from 1990-1997. Doborah is the author, with W. Meredith Long, of The AIDS Crisis: What We Can Do (2006), as well as Kidnapped (1975), which chronicles her 1973 abduction with her husband by the Eritrean Liberation Front while they were working as missionaries.

What’s going on at the border?

The following is a reflection written by John Miller, Immigration Specialist at World Relief Seattle. He is accredited by the Department of Justice to practice immigration law.

Things have felt a little different for me since I’ve been back from Mexico. It’s hard now to read these ideologically-charged news stories about “The Wall” and “The Border” without seeing the faces of the people I met while I was in Tijuana.

I went to Tijuana to meet up with three other World Relief staff members from three different World Relief offices around the country. We convened near the border to partner with a local organization called Al Otro Lado, one of the leading organizations on the ground in Tijuana that provides support to people approaching the US border to apply for asylum. The four of us were selected for this trip because our expertise and credentials with practicing immigration law.

Each morning, we would enter El Chaparral, the infamous plaza in Tijuana, located directly before the border crossing point of entry. I use the word “infamous” because it has essentially become a massive waiting room. But in this particular waiting room, one doesn’t pull a number from a small machine and wait a few hours before speaking to someone. There aren’t chairs to sit on, and there isn’t a receptionist waiting there to help you. In fact, there aren’t staff there to assist you at all. El Chaparral is an uncovered slab of concrete where people from all over the world wait, for weeks or months, before they are allowed to approach the US border to apply for asylum.

Five years ago, if you went to any point of entry along the border to present yourself to US immigration officials and ask for asylum–the “correct way,” as laid out by US immigration law–you would have been taken into the custody of the U.S. government until the next decision had been made on your case. Today, if you go to the border to apply for asylum, you will be told to turn around and put your name on a list to get a number, or even told that you can’t apply there and you need to find another point of entry. You will likely end up in Tijuana, where you would spend the next 3-9 weeks of your life sitting around in El Chaparral, waiting for your number to get called.

This business of getting a number before applying for asylum is a recent phenomenon. U.S. immigration law has stated for decades that any person can approach any border crossing point of entry to apply for asylum. Turning someone away who fears for their life and may have a viable asylum claim is a violation of our own law. This new process also forces people to go through Mexican border officials first in order to gain access to U.S. authorities, which can put people, especially those from Mexico, in increased danger of exploitation and persecution. The physical list being passed back and forth between Mexican and American authorities is ripe for bribery and exploitation.

Our team spent the mornings meeting with individuals and families who were moored in El Chaparral, waiting on their numbers. We gave short presentations on the basics of asylum and what to expect after entering U.S. custody. Next, we met with individuals and families to answer further questions. For each person we spoke with, we gave instructions and directions to Al Otro Lado’s office, so that they could come later to get a free orientation and a free consultation with an immigration practitioner. We spent the afternoons doing one on one consults, learning each person’s story and discussing the exact claim to asylum that the person may or may not have.

One man I met with, who I’ll call Francis, had fled his country in western Africa just two weeks prior to our meeting. When I started our meeting by asking him what country he was from, the whole story came pouring out, the living nightmares that he had survived, and how he escaped. Everything he shared was so fresh. I asked Francis how long he had been waiting in Tijuana. When he told me that he arrived in Tijuana that very morning, it dawned on me: I was the very first person to hear what had happened to him. Here he was, on the other side of the world from his birth place, without anyone he knew, no Spanish ability, no legal authorization to work in Mexico, and no sense of how long he would have to wait before applying for asylum, and I, a total stranger, was the first person to hear his story. I was amazed by his resilience, conviction, and his willingness after everything to stand up for what is true and right. While it was difficult to hear the torture he had endured, I was able to share some good news: the supervising attorney and I both agreed that he had a very strong case. “Your case is very strong,” I encouraged Francis, “and the immigration judge may agree with us that you meet the legal definition of asylum on multiple grounds. Keep moving forward and don’t lose hope.”

I can’t read the news anymore without thinking of Francis’s face: the tears in his eyes, and the strength in his eyes. I think of the Guatemalan family I met in the plaza: the fear in the young mother’s voice, pleading with me to know if there was any way for the family to stay together after passing into US custody, and her fierce, protective love for her kids. I think about the newlyweds from Honduras and the single dad from Cameroon and the nineteen-year-old nursing student from Russia and the minor from Nicaragua who was traveling by herself. These aren’t just news stories about policies, budgets, or political division: they are stories of real people.

The situation is dire, but there is hope. There are organizations like Al Otro Lado who are on the ground, meeting, educating, and equipping the long line of asylum seekers in Tijuana. There are World Relief offices around the country supporting asylum applicants, both inside and outside of immigration detention. And above all, I know that the people I met in Tijuana are some of the strongest people I’ve met, and that gives me hope.

For many immigrants, arrival to America is not the end of navigating the complicated U.S. immigration system. That is why our office has expanded our Immigration Legal Services team from one to three full-time staff who are Department of Justice accredited over the last year. Assisting refugees, asylees and immigrants with work authorization, family reunification, and citizenship are just a few of the services this hard-working team does for newcomers. With your support, we are able to offer these services either pro-bono or at reduced rates to those in need.

Forging Resilience through Trauma

As an early employment specialist with World Relief, I get an in-depth look at the resilience found in refugees who arrive in America. I am privileged to see the human spirit overcome and persist in the face of overwhelming odds. While my work is intended to equip our partners as they establish financial stability, it also targets the insidious activity of injustice that has been sown in the lives of so many people.

Khalid* is one of these brave people, willing to give us a glimpse inside his story.

Khalid’s Story

As we begin, Khalid sets his drink down on the table in front of him and looks me in the eyes, “I don’t ask for anything, I just need protection. We need safety; that is all. This is my story.”

Khalid was born, and lived for many years, in the Nuba Mountains of Sudan. When he speaks about his home, his face lights up. Throughout our conversation, he continually reminds me, “the day there is peace, I will go back.” His love for his home pulses through him, despite how deeply the conflict of Sudan has wounded him.

When he was in his early twenties, the violence in Sudan became too much for Khalid to bear. He fled, finding safety in Egypt for a few years, but even there it did not last long. As the influx of outsiders stirred up resentment from the Egyptian government, Khalid found himself fleeing again; this time with his two boys, wife and two month old daughter. Quickly, he gathered his family and the few items that they could carry and journeyed toward the border.

Arriving at the border, things quickly descended into chaos. They had been spotted by local security forces. Shifting in his chair, Khalid recounts how people with him were struck by gunfire and killed that night. One man got hit through the throat, another through the knees. Khalid said he stopped to carry one of the wounded but could not get far.

Eventually Khalid made it across the border with his two month old daughter safely in his arms, but his wife and boys were overtaken and arrested by security. Khalid stayed and worked to pay for his family’s release while also working on his application as a refugee for resettlement in the U.S. In 2017, he received approval to come the U.S. with his youngest daughter. Meanwhile, his wife and two sons were released and sent back to Sudan.

Throughout the next few years, Khalid’s family lived on the run. Unable to return to their home in Sudan and still fleeing violence in Sudan, they started toward a large refugee camp in Kenya. Thankfully, they have now found safety and are waiting to be reunited with Khalid. Khalid’s deepest desire is to find a way for them to join him in America. It has been over ten years since he has seen them.

Forging Resilience

Khalid is a survivor. He has pushed back against the odds and grasped hold of opportunities. After faithfully attending our job readiness class, he was hired for a third shift job at a plastics molding company. Through culture shock and fatigue, he persevered. Under the weight of trauma, he forged greater resilience.

When a person is forced to flee their home to find safety, there is a series of shifts, internally and externally, in their identity. Not only is their lengthy journey to safety marked with physical and psychological trauma, it is punctuated by a sense of hopelessness that can lead them to doubt their own efficacy. Those experiencing forced migration have been through tremendous challenges.

That’s why, at World Relief, we seek to lighten the load of these vulnerable refugees, immigrants and asylum-seekers as they get back on their feet. In each of our programs we seek to help individuals uproot self-doubt, restore an awareness to their own strength and help address the many needs of those who have undergone this trauma. We are not the hero in this story of resilience, but what we do provide is an opportunity for them to harness their own strength to succeed. And we have an incredible front row seat to witness their journey.

Rebuilding Lives

Upon arrival in America, our ‘clients’ enroll in English Language classes (ESL) and employment services. This training takes place in community-based classes, which promote English acquisition, teach about U.S. workplace culture, and foster a community of survivors. These classes offer a support system for those overcoming trauma by intentionally establishing routine and community. In this environment, friendships form between people from some of the most dangerous conflict zones in the world. These friendships are crucial because it makes adjustment to a new home more manageable. It provides solidarity as resilient people band together, learning a foreign language and understanding the many nuances of a new culture.

With friendship and community many find they have the support and confidence they need to continue pursuing independence and secure employment. We firmly believe employment has the power to restore dignity and fulfillment in the heart of individuals as well as provide a sense of purpose in everyday life.

Not only do we aim to create a strong foundation for those we work with, but we also seek to provide wrap around assistance such as: arranging appropriate housing for refugee arrivals, enrolling children in school (often for the first time,) providing trauma counseling, and coordinating access to medical care.

Our goal is to help overcome the effects of violence, poverty and injustice lingering in the lives of individuals we serve through love in action. We refuse to believe injustice will always have a powerful grip on individuals’ lives and we are compelled to fight tirelessly to ensure that all people can experience the fullness of life God intended for them.

*Khalid’s name has been changed to ensure his privacy.

Dan Peterson currently works as an Early Employment Specialist for World Relief Dupage/Aurora. He has been in this role since January 2016. Before working for World Relief, Dan graduated from Worldview Centre for Intercultural Studies in Tasmania, Australia, where he received a B.A. of Cross-Cultural Studies.