Stories

Tim & Terri Traudt

A growing family

The following is a reflection written by Liz Hadley, Employment Specialist at World Relief Seattle.

Pulling up to the McGlashan’s house, it seems as though you’re looking at the perfect retirement set up: a lovely house set on a quiet suburban street with two massive golden retrievers bounding out the front door. Their home appears to be a place to hunker down and, with the kids all out of the house, enjoy the life phase you’ve planned for years.

But in retirement, Lisee and Doug’s family is actually growing: they welcomed two boys into their family last year, and more are being added to the family every few months.

The two young men pulling up into Doug and Lisee’s driveway seem by all accounts, typical young men: driving a nice car, sporting their favorite soccer team’s jersey, eager for the pizza to be delivered. But as they hug Doug and Lisee saying “hi mom, hi dad”…I’m suddenly aware that we’ve met a family with an incredible understanding of what ‘family’ means.

These two young men, Kwaku and Arafat, are both from Ghana. Doug and Lisee are from the US. Having met only a few months ago, they call each other by familial terms now: “these are our boys” Doug and Lisee will tell you; “for me, they are my mom and dad” Arafat explains.

This unlikely family began from a bit of humorous rejection as Doug explains. Having signed up to be a Cultural Companion with World Relief, Doug was paired with a young man who had just been granted asylum. After trying to meet up a few times and begin building a relationship, the connection fizzled out as the young man quickly became busy with work and English classes.

So Doug tried again.

This time, it seemed that the new potential match wasn’t too interested in having a cultural companion. Three times Doug put himself out there as a cultural companion to no avail, leading him to begin wondering with a smile and slight laugh if it wasn’t him that was the “issue”. But time has a way of working things out, and Doug’s persistence led him to befriend and come to love an unlikely group of young men who, far from their own families, have come to see Doug as a father and Lisee as their mother here in their new nation.

In the summer of 2017, World Relief introduced Doug to Arafat. When you meet Arafat, you meet a gentle, kind and pensive young Ghanaian who stands tall above you, offers a radiant smile and speaks in what feels like an impossibly low register. During their first meeting together, World Relief’s Cultural Companion Coordinator sat with them to help with the admitted awkwardness of meeting a stranger for the first time, but after that they were on their own! And lucky for Doug, this match stuck.

In their first few times meeting up, Arafat referred to Doug as “Sir”…but the formality didn’t suit Doug. In searching for a new way to refer to one another, Arafat asked if he could call Doug “dad”, This time, the term seemed fitting.

Conversations quickly turned to classic father/son topics: what to look for when buying a car, plans for furthering your education, understanding what’s happening on the field at an American football game, and what qualities to look for in a partner.

Arafat grew to know Lisee as well and naturally referred to her as “mom”. When I met with the family over pizza to hear their story, Arafat explains to me that he lost both his parents when he was young. He grew quiet and, in a manner fitting of a toast, described how much respect he had for Doug and Lisee, how much they had helped him, welcomed him and loved him. Turning to look at Doug and Lisee, Arafat said “I love you dad, I love you mom.” It was all I could do to not drown my slice of pizza in tears.

On the kitchen counter when you walk into the McGlashan house, sits a little shrine capturing their family: a photo of their adult daughter, a picture of their two Goldens, and a small balloon that says “I love you mom”. Lisee explains to me that this gift is from her boys. For Mother’s Day this past year, Arafat brought over flowers, a massive teddy bear, and this balloon. The balloon now sits amongst the mementos to biological children and pets they’ve cared for over years. It’s clear that the concept of family is being blown wide open for the McGlashans.

It’s not only Arafat whose been added to the family though–he has the natural ability and tendency to connect people. In being resettled by World Relief, Arafat was placed in an apartment with a handful of other young men, many of whom are now his close friends. As a bit of a leader amongst the apartment, Arafat began introducing his friends to Doug and Lisee, and over time and several shared meals, these young men also grew to trust and love the McGlashans, calling them mom and dad as well. When Doug and Lisee now talk about “their boys”, it’s this group of young men they’re referring to.

To be honest, when I first heard the “mom and dad” thing, I was a bit skeptical and wondered how deep these relationships had actually gone. Lisee shared with me a story from early on in their relationship though that reminded me of something my parents would do for me, thus dispelling my skepticism. Over the summer, Doug and Lisee took a vacation and were without cellphone coverage for a few days. During their time away though, they just had to find reception and call their boys to check in and see how everyone was doing. It turned out everyone was doing just fine, but one of the boys was anxiously waiting for them to return home so he could get their advice on a potential car purchase. After all, he had promised before they left not to make the purchase without first running it by them. It’s a subtle gesture – calling just to check in – but it communicates volumes. Arafat and his friends never expected to have this in America: someone who would call just to check in, just to say hi, just to remind them that someone cared for them and saw them. Hoping to find safety in America, they had also found family.

The other young man joining us for pizza today is Kwaku, another Ghanaian who Arafat met through World Relief, and another one of “the boys”. Kwaku

and Arafat didn’t know each other back in Ghana. Though from the same city, they had grown up in different communities; one being raised in a Muslim community, the other in a Christian community. Today before sitting down to eat, we all stand in a circle, hold hands, listen to Doug’s blessing, and finish in a collective “amen”, feeling quite naturally at home and at ease with one another.

Kwaku and Arafat both came to the United States seeking the protection of political asylum. Fearing for their lives for different reasons, they both left their country on a plane headed to Brazil where they would begin their journey on foot…all the way up through Central America to the US/Mexico border. It’s there that they asked for asylum.

In writing this story, I attempted to look up how many miles their journey took them – walking from Brazil to Tijuana. Google Maps tells me “walking route not available”.

When I ask them, Kwaku and Arafat have no idea how many miles it was; for Arafat, the journey took about three months, for Kwaku it took four months. Over our lunch at the McGlashan’s they share with us a bit about the journey, naming off the countries they passed through as if it’s a geography quiz: “Brazil, Ecuador, Columbia…”

Every time I listen to an asylee recount the story of their journey to the US, without fail they each grow quiet when they speak of Panama – “The jungle…you have no idea what I have seen there…”

Along the border of Columbia and Panama lies the Darién Gap, a nearly 60-mile section of dense rainforest. For more than a century, humans have tried to tame the jungle in the Darién Gap, but the jungle has consistently rejected their efforts. This portion of the trek north for asylum seekers is by far the most perilous: those on the journey blindly follow a path through the jungle for days, hardly daring to stop and sleep for fear of what might come upon them. For days they push on: “you can’t stop, you just have to keep walking.” Some migrants carry a bag of sugar with them on this leg of the journey, eating spoonfuls to keep them awake and moving. Robbers, drug traffickers, smugglers, animals and the elements can meet you on the path…it’s better to move through as quickly as possible.

The journey through the jungle crosses wide rivers, two mountains and is strewn with discarded items that migrants who have come before deemed too much to carry. The way is also marked by graves. Arafat keeps his eyes on his plate while he tells me of one woman he journeyed with being bitten by a poisonous snake. “We didn’t have any medicine”, he explains. He describes another night in the jungle when their group was ambushed and searched for money and valuables. He smiles a bit proudly as he recounts to us how he had split up his money between the lining of his hoody and inside his shoes so as to evade a search like this one.

Kwaku’s journey to the US took a month longer than Arafat’s, owning to the fact that in one country, police intercepted him and deported him back to a neighboring country. For most people, this set back is too demoralizing, Kwaku explains. Many people have struggled on the journey too much and feel they don’t have the energy or courage to retrace their steps. They give up and retreat back home, resigning themselves to the danger awaiting them there. But for Kwaku, he pressed on.

As he recounts a bit of his journey, it reminds me of stories from the underground railroad: a kindhearted stranger offers shelter for the night and bread for the next day’s journey; a bus is pulled over and searched because passengers explained to police that there are “black men” on board. And one puzzling story in which a border patrol agent slips him a piece of paper with Spanish scribbled on the back. He’s quickly told to show this paper to agents if he’s detained at the next border, but he forgets this prompt and sits for several hours in a jail not sure if this is the end of his journey. Suddenly remembering the paper, he shows it to agents and is freed to continue on his journey. To this day, he’s not sure what was written on the paper.

Having made it to the US border, Kwaku and Arafat both began the process of seeking asylum, a process which involves being handcuffed and taken to a detention facility. Both expressed to me their shock around this treatment. Arafat motions to his wrists and ankles explaining how he didn’t imagine that in the US he would feel like a criminal. After waiting months in the Northwest Immigration Detention Center – a facility where the lights are never turned off, even for sleeping, and you’re paid $1 a day for your work – both Kwaku and Arafat won their cases, were granted asylum, and allowed to begin their lives in the US.

Through World Relief’s Asylee Resettlement program, they both worked with a caseworker to secure housing, apply for documents and become oriented to their new community. They enrolled in English classes, employment services, and luckily for the McGlashans, were open to meeting other Americans through the Cultural Companion program.

Both Kwaku and Arafat now work as security guards at a prominent Seattle security company and balance hectic schedules of night shift jobs and college classes. Kwaku has already been promoted at his job and Arafat was offered a promotion, but in wanting to give the company his best, he decline the offer explaining that he wanted to improve his English before taking on the position. True to the example other asylees have set before them, Kwaku and Arafat are incredibly hardworking and jumped right in to the work of rebuilding their lives.

Before meeting Arafat, Doug and Lisee had never met an asylee before, let alone fully knew what the term meant. Over lunch, we ask about their experience through all of this, what it’s been like to build this relationship which started as a formal “cultural companion match” and has grown into an authentic relationship.

“We’ve received so much more than we’ve given…how rich it is for us, to have their stories as part of our stories now” Lisee explains.

Addressing Kwaku and Arafat, Doug explains, “It’s inspiring, because when you hear what you’ve been through to get here, I can’t imagine what it took to survive that. And then when you arrive here, it’s so gratifying to see how you take on your dreams and ambitions. It’s an honor to watch you become who you want to be….it’s wonderful to be together like a family and watch our relationship grow.”

Welcoming Refugees is Everyone’s responsibility

The first time I celebrated World Refugee Day was June 20, 1997, along with thousands of others in Nyarugusu Refugee Camp, Kigoma, Tanzania. A child at that time, I did not really know what it was for or why people celebrated it. Looking back, I realize that the children’s poems and plays, speeches from the camp community, government leaders, and U.N. officials spread a message of hope and a call to action to the nation and the globe. Since the world’s response to this humanitarian crisis had been effectively crippled, this day helps to create awareness. Telling my own story is part of raising awareness – and that’s why I’m here, writing.

Over the course of my life, I’ve lived in several places and countries – so I didn’t expect to experience anything particularly new or different from what a refugee or an immigrant normally feels upon arrival in a foreign country. But nothing could have prepared me for my experience arriving in Memphis.

It was completely different than I imagined. I was welcomed into a friendly environment that continues to have a huge impact on my life to this day. As a Christian, I was afraid of the challenges that I could face and the impact of living in a secular country could have on my faith. But World Relief, the resettlement agency through which I was resettled in the U.S., connected me with volunteers and other community members who share the same faith. These people opened their arms and homes to me, inviting me to share meals and stories with them. It was a huge contrast: Before being invited to the U.S., I lived in South Africa for about 4 years, and during that time, I never entered a South African friend’s home.

I will confess, I was not greatly impressed by the city or buildings when I first arrived in Memphis. What did impress me was how people welcomed me and the love they showed me. I never felt lost on my first days in the U.S., thanks to the opportunity World Relief gave me to connect and hang out with new friends. They made my transition very smooth, and I am grateful for that.

That said, not everyone has an easy and smooth transition when they move to a new country. The majority of the refugees in my current community in Memphis came from refugee camps, where they lived for an average of about two decades. These camps are like living in an open-air prison. Not only are the medical system, nutrition and education poor, but people there are kept in the dark about almost everything. They have no idea what is going on around the world.

Arriving in the U.S. after spending many years in the refugee camp is a shock. The amount of new information and the pace at which you have to learn it is overwhelming. Some refugees have limited knowledge of the new language and are unable to navigate the public system on their own after the orientation services provided by their resettlement agency end.

Having been once in their position of vulnerability and confusion, I see it as my duty as a human being and a member of their new community to care for and support them as much as I can. It is a means of giving back. It is a means of serving my community. It is a form of showing love. It is a form of showing there is always a place they can run to for help – a hard lesson to learn after living in a refugee camp.

This is what all of us are called to and what all of us should be doing. If you’ve grown up outside a refugee camp or if you’ve lived a comparatively comfortable life in America, it can be hard to imagine how a small gesture of kindness and love can eternally impact the many broken lives out there – but it impacted mine. In fact, gestures like these are one of the reasons I decided to buy a house in Binghampton, the most diverse community in Memphis. I believe that the first step of commitment in serving a community is to live within the community, so that we can strive and face challenges together.

With the world in constant crisis – wars, natural disasters, persecution, famine and the mass migration of refugees resulting from these – it is inhuman to cross our arms and say, “This is not my problem.” If it is not your problem, whose problem is it? It is the responsibility of all of us to care for and offer our support to those who are suffering around the world. Not one refugee desired to be in the situation they are now. They simply wanted to live and be free – just as Americans do.

Twenty-two years after that first celebration in the camp, World Refugee Day remains very important to me. Just like the children in the camp singing their songs and the U.N. officials making their speeches, I raise my voice to tell the world about the refugee crisis and demand a collective response. There will never be a better time to act than now.

Basuze Gulain Madogo was born in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and first fled with his family for refuge in 1996. He was invited to be permanently resettled in the United States in 2014. Since being welcomed to Memphis, two brothers have joined him here, and two additional brothers have been resettled in Massachusetts and Wisconsin. He was hired by World Relief Memphis as a Resettlement Specialist in 2016, graduated with an Associate Degree from Southwest Tennessee Community College in 2017, and is studying Accounting at the University of Memphis. Join Basuze and World Relief by supporting our work of welcome. Visit HERE to learn more.

What’s going on at the border?

The following is a reflection written by John Miller, Immigration Specialist at World Relief Seattle. He is accredited by the Department of Justice to practice immigration law.

Things have felt a little different for me since I’ve been back from Mexico. It’s hard now to read these ideologically-charged news stories about “The Wall” and “The Border” without seeing the faces of the people I met while I was in Tijuana.

I went to Tijuana to meet up with three other World Relief staff members from three different World Relief offices around the country. We convened near the border to partner with a local organization called Al Otro Lado, one of the leading organizations on the ground in Tijuana that provides support to people approaching the US border to apply for asylum. The four of us were selected for this trip because our expertise and credentials with practicing immigration law.

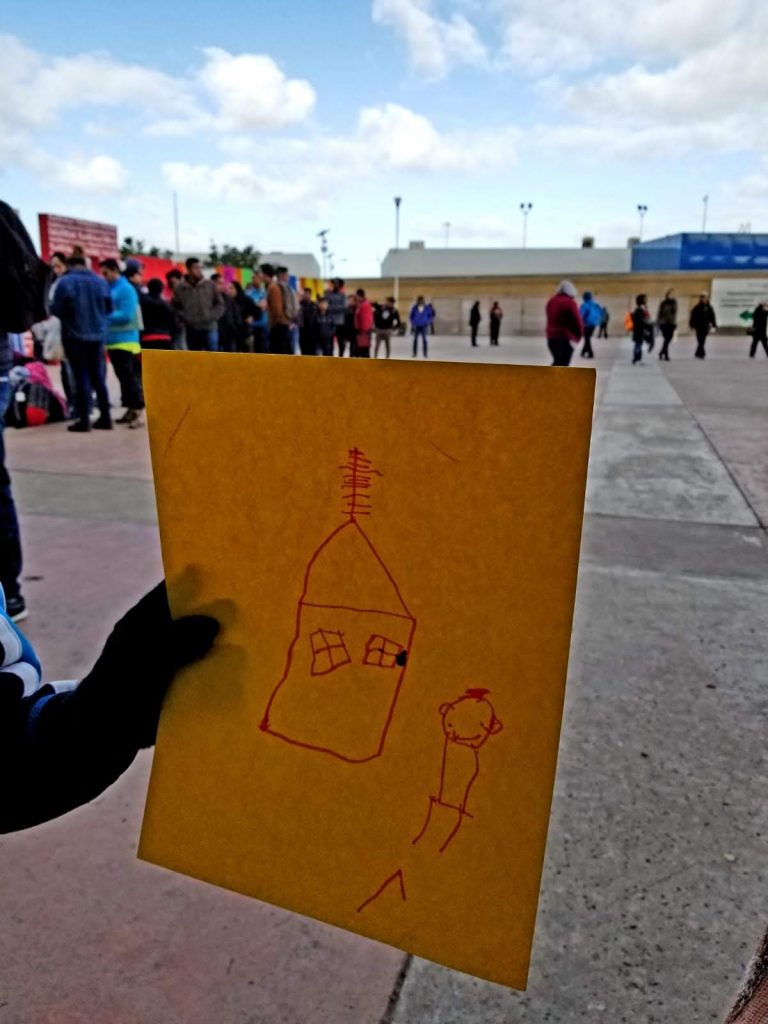

Each morning, we would enter El Chaparral, the infamous plaza in Tijuana, located directly before the border crossing point of entry. I use the word “infamous” because it has essentially become a massive waiting room. But in this particular waiting room, one doesn’t pull a number from a small machine and wait a few hours before speaking to someone. There aren’t chairs to sit on, and there isn’t a receptionist waiting there to help you. In fact, there aren’t staff there to assist you at all. El Chaparral is an uncovered slab of concrete where people from all over the world wait, for weeks or months, before they are allowed to approach the US border to apply for asylum.

Five years ago, if you went to any point of entry along the border to present yourself to US immigration officials and ask for asylum–the “correct way,” as laid out by US immigration law–you would have been taken into the custody of the U.S. government until the next decision had been made on your case. Today, if you go to the border to apply for asylum, you will be told to turn around and put your name on a list to get a number, or even told that you can’t apply there and you need to find another point of entry. You will likely end up in Tijuana, where you would spend the next 3-9 weeks of your life sitting around in El Chaparral, waiting for your number to get called.

This business of getting a number before applying for asylum is a recent phenomenon. U.S. immigration law has stated for decades that any person can approach any border crossing point of entry to apply for asylum. Turning someone away who fears for their life and may have a viable asylum claim is a violation of our own law. This new process also forces people to go through Mexican border officials first in order to gain access to U.S. authorities, which can put people, especially those from Mexico, in increased danger of exploitation and persecution. The physical list being passed back and forth between Mexican and American authorities is ripe for bribery and exploitation.

Our team spent the mornings meeting with individuals and families who were moored in El Chaparral, waiting on their numbers. We gave short presentations on the basics of asylum and what to expect after entering U.S. custody. Next, we met with individuals and families to answer further questions. For each person we spoke with, we gave instructions and directions to Al Otro Lado’s office, so that they could come later to get a free orientation and a free consultation with an immigration practitioner. We spent the afternoons doing one on one consults, learning each person’s story and discussing the exact claim to asylum that the person may or may not have.

One man I met with, who I’ll call Francis, had fled his country in western Africa just two weeks prior to our meeting. When I started our meeting by asking him what country he was from, the whole story came pouring out, the living nightmares that he had survived, and how he escaped. Everything he shared was so fresh. I asked Francis how long he had been waiting in Tijuana. When he told me that he arrived in Tijuana that very morning, it dawned on me: I was the very first person to hear what had happened to him. Here he was, on the other side of the world from his birth place, without anyone he knew, no Spanish ability, no legal authorization to work in Mexico, and no sense of how long he would have to wait before applying for asylum, and I, a total stranger, was the first person to hear his story. I was amazed by his resilience, conviction, and his willingness after everything to stand up for what is true and right. While it was difficult to hear the torture he had endured, I was able to share some good news: the supervising attorney and I both agreed that he had a very strong case. “Your case is very strong,” I encouraged Francis, “and the immigration judge may agree with us that you meet the legal definition of asylum on multiple grounds. Keep moving forward and don’t lose hope.”

I can’t read the news anymore without thinking of Francis’s face: the tears in his eyes, and the strength in his eyes. I think of the Guatemalan family I met in the plaza: the fear in the young mother’s voice, pleading with me to know if there was any way for the family to stay together after passing into US custody, and her fierce, protective love for her kids. I think about the newlyweds from Honduras and the single dad from Cameroon and the nineteen-year-old nursing student from Russia and the minor from Nicaragua who was traveling by herself. These aren’t just news stories about policies, budgets, or political division: they are stories of real people.

The situation is dire, but there is hope. There are organizations like Al Otro Lado who are on the ground, meeting, educating, and equipping the long line of asylum seekers in Tijuana. There are World Relief offices around the country supporting asylum applicants, both inside and outside of immigration detention. And above all, I know that the people I met in Tijuana are some of the strongest people I’ve met, and that gives me hope.

For many immigrants, arrival to America is not the end of navigating the complicated U.S. immigration system. That is why our office has expanded our Immigration Legal Services team from one to three full-time staff who are Department of Justice accredited over the last year. Assisting refugees, asylees and immigrants with work authorization, family reunification, and citizenship are just a few of the services this hard-working team does for newcomers. With your support, we are able to offer these services either pro-bono or at reduced rates to those in need.

A Myth of Scarcity

The following reflection is written by World Relief Seattle intern, Aubrey Payne. Aubrey spends her days with World Relief accompanying people on appointments, helping out in English class, building relationships with newcomers, and otherwise assisting in the resettlement process.

Every day that I spend with the participants at World Relief, I am reminded of the generosity that comes from God’s abundance.

Recently, I took a single mother from Afghanistan to a gruelingly long appointment at the Department of Social and Health Services. She and I met with three different employees in a process that took over 5 hours, only to find out that she was being denied food stamps. The baby was tired and cranky, as were we, and the mother broke down in tears. The weight of her situation–as an immigrant with very little money, trying to start a new life for herself and her baby–started to sink in. We got in the car to drive home. In an expression of gratitude for my time, she gave me a handful of chilgoza–a type of pine nut found in Afghanistan and which costs about $20 per bag.

In The Liturgy of Abundance, the Myth of Scarcity, Walter Brueggeman writes, “What we know about our beginnings and our endings, then, creates a different kind of present tense for us. We can live according to an ethic whereby we are not driven, controlled, anxious, frantic, or greedy, precisely because we are sufficiently at home and at a peace to care about others as we have been cared for.” The truth is, many people will never feel like they have enough. We place a high value on work and busyness in America, often believeing that we do not have enough time or resources to care for others the way Jesus did.

The generosity demonstrated to me by a tired Afghan mother is the kind of generosity I see every time I meet with the refugees and immigrants who come through World Relief’s doors. Because a belief in God’s abundance far exceeds the restrictions imposed by the economy or personal finances, this woman felt moved to share a cultural delicacy with me, even though she had so little to offer. When we believe in the good news of God’s abundance, there are no more excuses for living a greedy and un-neighborly life. If we believe in a God that loved the world into generous being, then we can live in the knowledge that there is enough to go around to everyone. It is a different kind of present tense. We can be at peace to care about others as we have been cared for, even if that just looks like a handful of precious pine nuts.

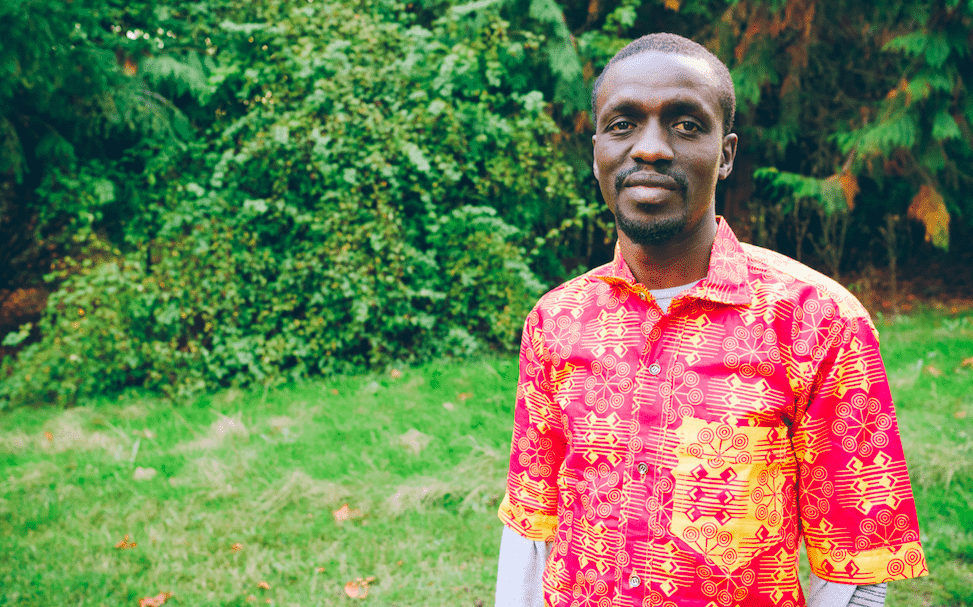

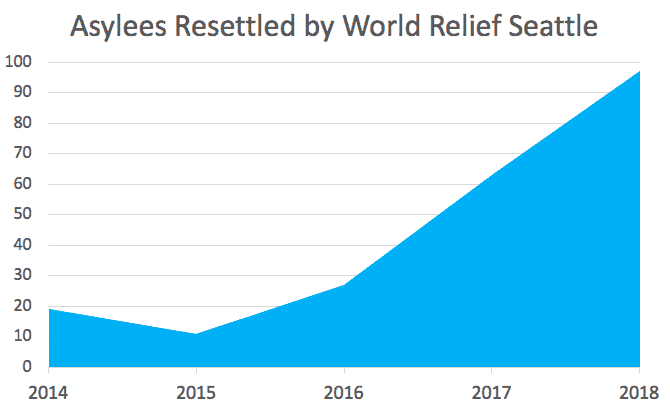

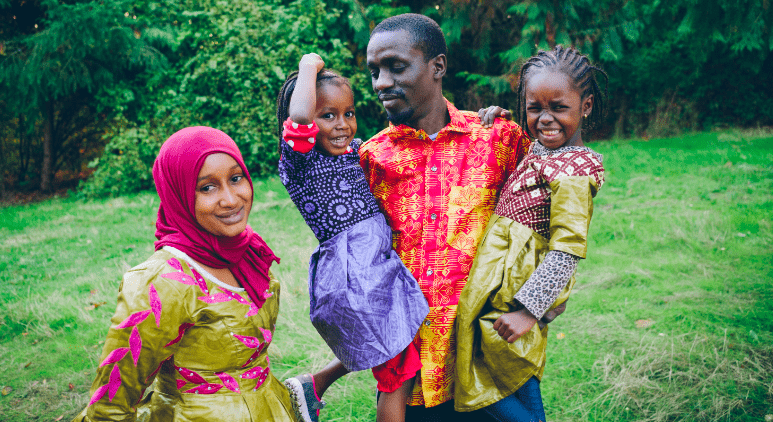

Asylees in Seattle

After spending months in the Immigration Detention Center in Tacoma, Mamadou still had more waiting to do. A federal judge had granted him asylum, and he was now free to start his new life here in America, but his life wasn’t whole. He fled political persecution in Guinea 4 years ago when a gathering at his home was violently dispersed. Staying meant torture and the possibility of death. Fleeing meant leaving behind his young daughter and pregnant wife. It was a choice nobody should have to make. When describing that decision, Mamadou shared that, “I was leaving my poor family in terrible fear.” We are seeing this kind of decision forced upon thousands of people who have to choose between safety and remaining in their country.

Home by Warsan-Shire

“No one leaves home unless

home is the mouth of a shark

you only run for the border

when you see the whole city running as well…”

Mamadou’s desperate journey took him halfway around the globe. His flight to safety is similar to the journey of the asylum seekers currently at the border that are being shown on the news right now. Their stories are often politicized rather than understood as a complex choice made by people in desperate situations.

This global crisis becomes a local reality when people like Mamadou turn themselves in at the border and are then handcuffed and transported up I-5 to the detention center in Tacoma. Thousands of people passed through that facility this year, and about 80% of them were deported back to their country of origin. We have seen a great increase in the number of people being detained, and the number of people in need of encouragement, care, and connection to resources. Our volunteers came alongside 4,025 individuals while they were in detention this past year. some of whom were parents who had bee separated from their children at the border.

You have to understand,

that no one puts their children in a boat

unless the water is safer than the land

no one burns their palms

under trains

beneath carriages

no one spends days and nights in the stomach of a truck

feeding on newspaper unless the miles travelled

means something more than journey.

no one crawls under fences

no one wants to be beaten

pitied

Finally, this summer, Hassatou and the two young girls arrived to Washington. Mamadou met his youngest for the first time. He held his wife at last. His family was finally whole and safe. Their journey is not over though: Hassatou and the girls are beginning to learn English, Mamadou is making ends meet to afford a bigger apartment for his family, and they are together building a new community of friends and neighbors.

Will you join us helping newcomers like Mamadou, Hassatou, and their girls meet these challenges?

If You Plant Early, You Harvest Early

“If You Plant Early, You Harvest Early”

The first son of a large family, Daoud’s father raised him implementing the Afghan Proverb that “if you plant early, you harvest early.” Daoud apprenticed in his father’s trade and was entrusted early with responsibilities in his father’s store. He married young, grew the family business, had children, went back to finish school, and started studying English. Following carefully laid plans, his life was on track: he was beginning to harvest early.

But new conflict and war came to Afghanistan. Daoud’s business suffered and the harvest was no longer abundant. In order to provide for his family, Daoud took a risky job translating for the Coalition Forces. His careful plans to study English proved beneficial, even though those years were fraught with uncertainty. As time went on, it became evident that his family’s safety was precarious. He learned his job with the Coalition Forces made them eligible to apply for resettlement in the United States, so once again, they began making plans. It took two years for all the paperwork, background checks, medical checks, and security clearances to be completed, but Daoud and his family were relieved to receive their Special Immigrant Visas to relocate to the USA, to Memphis. [The U.S. offers a Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) program to individuals who have been employed by or on behalf of the U.S. in countries like Afghanistan and Iraq, and is awarded in recognition of their sacrifice.]

Daoud knew before moving to the United States that America is the land of opportunity and that if he worked hard, they would make it. He remembers the night they arrived in June 2014; they were greeted by World Relief caseworkers, volunteers and new neighbors, all welcoming them. As modeled by his father, Daoud immediately began planting seeds to succeed in the United States. Step one was to support himself and his family financially. He started working full time in a warehouse loading trucks. Although he had skills to do so much more, he understood finding your first job in the United States is not easy and he was determined to do whatever required. Not long after he began working, Daoud had to have major surgery. Even though it was a setback, he sees it as a blessing that he was in the United States when he got sick and was able to receive medical care. Back home it would have gone untreated.

Once Daoud recovered, he began “planting” and working again. He found full-time employment at another warehouse and took on another part-time job. Soon he was able to progress to step two: buying a house. After living in America for only two and a half years, Daoud and his family began to harvest from their plans and hard work. “We have experienced a better life here compared to Afghanistan. For example, our kids are in schools, we own a house, we got our rights, we have vehicles, all positive things that have happened. I am living the American dream. I never thought I could become a homeowner in two years!”

Daoud is continually motivated by his family. “Every parent hopes for their children to get an education, go to college, get a good job. My dream is for them to go to college and get a major that lets them serve the United States and Afghanistan.” He is teaching them to plant early for their future and prays that war does not disrupt their harvest. Daoud has also decided to return to school to complete his bachelor’s’ degree. He knows education is important and is applying what he is teaching his children to himself.

Before arriving in the United States, Daoud was afraid that he would not be able to worship freely here, that it would be challenging to be an immigrant and begin a new life with his family. But resettling in the U.S. was a blessing they never imagined possible. With help from World Relief, intentional planning, planting and hard work, they have adjusted well to life in the U.S. and this new culture – including new freedoms – discovering a community filled with friendship and love. Their journey has been long. Things did not all go as planned, but he and his family are thriving in this new place. They have been able to worship freely and Daoud’s family never take their new freedom for granted. “Freedom is a gift of God for humans,” he reflects. And only four years after setting foot on American soil, his family is harvesting early.

Catherine Gross, World Relief Memphis

Photos by Emily Frazier Creative

The most powerful teacher

The following is a reflection by Beth Watkins, World Relief Seattle Resettlement Intern.

I’ve thought a great deal about my hometown lately.

Being a fairly recent Seattle transplant, perhaps it’s simply homesickness finally kicking in. Perhaps the stark differences in landscape, the lack of familiar faces, and the infamous “Seattle freeze” are finally beginning to wear on me. Whatever the reason, home has been on my mind.

I come from a small midwestern town in southern Illinois with a population of about 500 people. It’s a largely agricultural community. Most people over the age of 60 still speak at least a little German. Once a year my entire town gets together to make and jar apple butter. Everyone is at least distantly related– there are probably a total of ten last names in the whole town. It’s a place that feels far removed from the rest of the world.

Last week I got to sit in on World Relief’s sewing class for the first time, and for a few hours, I was transported back to the Midwest, to quilting circles in church basements (albeit with a little more Dari than I remember being spoken at home). As I talked with the students and volunteers, I thought of my grandmother, who has hand-stitched multiple quilts for each of her children and grandchildren. It was so easy for me to picture her in this room of women, talking about fabric patterns and bragging about grandchildren. But as easy as it is to picture her there, I don’t think my grandmother will ever sit in a room full of Afghan women. Not because she doesn’t want to– she often expresses interest in my work at World Relief, asking about the people I’ve met and the things I’m learning– but because she lives hours from a major city with any detectable level of diversity. She’s simply unlikely to ever encounter a refugee in her daily life.

It’s easy for me to become angry at my community for being ambivalent or negative towards refugees…until I remember that my most powerful teacher has been my firsthand experiences with refugees themselves. These are experiences that many of my family members and neighbors will most likely never have, simply because they don’t have access to them. And while this doesn’t excuse prejudicial attitudes and behaviors, it does contextualize them. How can you come to care for someone you have never met, who is simply a theoretical idea, a conveniently distant scapegoat for economic disparity and a rapidly evolving cultural landscape?

My hope for my community is that somehow, eventually, they become personally connected to refugee communities. I hope they are allowed the same opportunities I’ve been given to sit with refugee families, to hear their stories, to stumble over language barriers, to share food and laughter and time together, to grow out of prejudice and into relationship. I don’t yet know what this looks like or how to make it happen–how to overcome physical distance and, in many cases, deep prejudice. I don’t know how these experiences will happen, but I know that the prejudice in my community will not change until they do. Until I find a way to bridge this gap, I can convey my own experiences and at least act as a small window into the lives of the refugees they have yet to encounter. I can act as a cultural broker for my own community, an invitation into a new way of being and moving through the world.

Beautiful Surprise

“What is friendship to you?”

Tigi looks at me for a moment while she thinks about the answer. She seems anxious that she may not be able to express herself fully in English, but she finds the right words.

“Friendship means helping each other when it is good news or bad news. [It means] sharing with your friends, and helping them. Even when there is nothing else to do, you can pray for your friend.”

Tigi has lived in the U.S. for almost three years now. Her husband has a steady job, they have had a baby here, and she is eager to start working again herself. They are involved in a small church with other Africans in the city. Tigi and her family have been building a joyful, humble life for themselves here. It took many people to help them get to where they are today. One of these people is Tigi’s friend Joy.

“I loved Joy on the first day [that I met her].”

Joy didn’t know what exactly to expect the first time she met Tigi and her family. She’d had experience volunteering with foreign-born people, and she knew she loved being around people from other cultures, but being a part of a Good Neighbor team was a bigger commitment. After hearing about World Relief while at her church’s missions conference, Joy said that “the seed was planted. I knew God was calling me to reach the world in Memphis.” Joy was at the airport when Tigi and her family landed in the U.S.

“The first thing I remember about meeting Tigi and her husband is that their smiles were just contagious. I started going to their house once a week to practice English, and they just welcomed me and my family right into their home.”

Joy and Tigi’s relationship grew over time. Soon, they were doing more together than practicing English. Joy recounts some of the fun things they’ve done together: “One time, we took Tigi’s family out for smoothies, which they thought were too sweet. But we also introduced them to Chick-fil-A, which they like a lot!”

It took time for Joy and Tigi’s friendship to grow, though. In addition to the language barrier, they faced other challenges. Tigi remembers when they first arrived in America, before she began staying home with her daughter: “At first, I was working and pregnant, and Joy came to my house. I worked night and she worked in the day, so it was hard to see each other. But it got better when I stopped working. She always asked how I was and how the baby was.”

For Joy, it has been hard at times to relate to Tigi and her experience: “One time, a few months into our relationship, Tigi was upset because she hadn’t gotten to talk to her mom in a long time, who isn’t in America. Before that, I didn’t realize how much she had truly left behind.”

But despite challenges in their unlikely friendship, Tigi and Joy and their families grew closer. They celebrated holidays together. Joy’s own mother was in the delivery room when Tigi delivered her child, which earned Joy’s mom the affectionate nickname “The Doctor” from Tigi and her husband Ibisa. Joy’s dad taught Ibisa how to drive. And the learning has been mutual, according to Joy. “I have learned a lot from them, especially about resilience, joy, and their love for the Lord.” When I asked her what her favorite thing about Joy is, Tigi said, “She likes all my food, which makes me feel loved.”

But the most inspiring part of Tigi and Joy’s story is what happened when Joy got married. In May 2017, Joy and Tigi had known each other for a year and a half, and Joy was deciding who she would invite to be a bridesmaid in her wedding. “I asked myself, ‘Who am I closest to? Which relationships in my life are flourishing?’ It wasn’t even a question, of course I had to ask Tigi!”

To ask Tigi to be in her wedding, Joy gave her a set of earrings shaped like little knots, with a card that said, “Will you help me tie the knot?” which Joy soon learned was an American idiom. “I had to explain what ‘tie the knot’ meant, but once Tigi understood what I was asking, she agreed and was very excited.”

It was Tigi’s first American wedding, and it did not disappoint: “It was very pretty, and I liked my dress. It was mostly the same as an Ethiopian wedding, but it was different because there was no dancing. That is okay, because sometimes there is too much dancing in Africa!”

—————————————–

When Joy first signed up to volunteer with World Relief, she wasn’t expecting to meet one of her future bridesmaids, and when Tigi was assigned to come to America with her family, she probably wasn’t expecting to be in an American wedding so soon. But their story is a testament to the amazing things that can happen when people are willing to get out of their comfort zone and come alongside the vulnerable.

Both Joy and Tigi had words of advice to anyone who might be hesitant to volunteer with refugees. Tigi said, “If it was me, meeting someone from a new place, and a new culture, I would be scared. Joy wasn’t. So don’t be scared. They [refugees] are the same as you. Maybe they have a different culture, language, or color, but that is a gift from God.”

Joy said, “I would say to them [someone fearful of volunteering] that God’s heart is for the nations. It is a mutual learning experience, but refugees are very gracious. They are friends. This whole thing has been a beautiful surprise, but I wouldn’t want it any other way. Tigi is family now.”

By Noah Rinehart, Rhodes College Bonner Scholar Intern

In honor of Volunteer Appreciation Week we have been sharing a series of inspiring stories, capturing how are volunteers and immigrant friends together are #loveinaction. If you would like to learn more about volunteering with World Relief, email our Volunteer Coordinator cbrinkley@wr.org.

A New Name

“The nations shall see your righteousness, and all the kings your glory, and you shall be called by a new name that the mouth of the Lord will give.” Isaiah 62:2

As we enter Volunteer Appreciation Week, we are sharing inspiring stories of relationships between World Relief Memphis volunteers and our refugee and immigrant community. We’re confident you’ll agree with us, our volunteers are #LoveInAction!

When refugees first arrive at the airport, it is often after a long travel journey of several flights and multiple days. This would be enough to leave the average person weary. But for refugees, this is really the end of a much longer journey, that usually includes fleeing home at the point of death, waiting for years in an underfunded, overcrowded refugee camp, and then spending a minimum of eighteen months applying for resettlement to a Western nation like the United States. Bien Fait, one of our former clients at World Relief Memphis, remembers this feeling: “Our flight was two days, we were very tired, you know flying for two days, it was a very, very big issue, because we have taken five flights. All the people, my children, were tired. Myself, I was tired. My wife, was very tired. But when we reach the airport of Memphis, we say, ‘Thank you, God.’”

Finally arriving to the airport in their new city marks the end of long, arduous journey for refugee families, but the beginning of a new one to build a life in America. And that journey requires the help and commitment of people like Melissa Peeler.

Bien Fait remembers when he met Melissa for the first time: “We met with Melissa Peeler and Michael on August 24, 2016. She came there [the airport], she received us, she was introducing herself to us. She say, ‘I am Melissa Peeler, I will be your volunteer, to show you everything in America, until you will know about America. And I will never give up, I will be with you everyday, everytime. If you have some questions, if you need some help, call me.’” He also remembers being struck by such a strong statement from someone who he didn’t even know, telling us, “It was the first time to make friends with a white man, to know American people. When she was coming and saying, ‘I will be your volunteer, your friend,’ I was scared, thinking, ‘Why will this white man be my best friend, my volunteer? What is going on?’”

Melissa remembers that day in the airport, too, and how she felt meeting Bien Fait for the first time: “You know, I honestly do not remember saying those exact words to Bien Fait that night, but I absolutely remember thinking that to myself before I committed to being on a good neighbor team and ever knew his name. I knew this was going to be a pretty big ‘volunteer thing’ and I took it seriously…I think I was so overwhelmed seeing them walk off the plane so late that very first night, and was just overcome with the raw emotion of their circumstance and how young and unsure Josephine and Bien Fait and the kids were – and just wanting to say something reassuring to Bien Fait. My heart leaps at the thought that he remembers that I said something that translated to, ‘I was committed to him and his family’ that night.”

Melissa’s promise was not in vain. She taught Bien Fait and his family many things. He humorously recalled the first time that Melissa showed him how to use a slow cooker: “She said, ‘Because you are in America, you should learn how to cook American food!’ She came with a pot, that had power for cooking, and she put all the stuff in this pot, and she said, ‘You have to wait one hour and twenty minutes, and then the food will be ready and you can eat it!’ We said, ‘What?! In Africa, we don’t cook like this! In Africa, we cook on the fire, and you put the pot over the fire, we need to see that something is boiling. How do you cook like this?’ and she said, ‘This is a good way to cook in America! People will leave the pot, and then go to church, and when they come back, they find that the food is already cooked, and eat it.’ I said, ‘Okay!’ She showed us, and we tried to get experience to cook this food.”

Melissa remembers those first few weeks being marked by difficulty: “In the very beginning, we were very much a needed helper – a driver, an appointment maker and taker, a school registrar and uniform finder, for what seemed like more than a few pretty intense weeks…but the more time we spent with each other, the more comfortable we got with each other and things naturally grew into a genuine fondness for each other.” Eventually, Bien Fait’s family was celebrating holidays with the Peelers. “Melissa’s was the first American home to visit. She invited us there. We went there with my whole family. The first day was for Thanksgiving Day. She said, ‘Please, I need all of you to come to my house! Thanksgiving Day we have to share together!’ So we went there, she provided some very, very, very sweet food, very good food, which we shared together with Michael and the children. After that, she said, ‘If anyone has something he wants to tell, because it is Thanksgiving Day, we have to say something, to say thank you to God, for what He did for you.’ It was our first time [to celebrate Thanksgiving]; in Africa we didn’t know about Thanksgiving…This was the first time, we found this in America. It’s good, it’s good!”

Bien Fait’s family has learned much about American culture from Melissa, but the Peelers have also learned a lot. “There are more small and medium things than I could ever say, but two of the most important things I’ve learned from the Mfaume’s is Faithfulness and Resilience. If you had asked me two years ago if I really understood what those words meant and if I had those qualities I would have honestly told you I did! I felt very faithful and comfortable in my faith walk and had overcome enough difficulties at the time to say I had built up quite a resiliency. MY WORD…it’s honestly laughable as I say that now, knowing the depths of the Faithfulness and Resiliency the Mfaume’s have. The devout trust and faithfulness the Mfaume’s have in God and his control in their lives is inspiring. I mean like big “I” Inspirational. They are grateful for every little blessing in their lives and talk about that openly and intentionally. They honestly put and continue to put their future in God’s hands daily. The patriarch of the family, Patient, had endured a pretty gruesome war injury and lost an eye that caused him terrible headaches and shooting pains down his neck. I never knew how much it hurt him until I accompanied him to the surgery consultation about repairing it. With the help of a translator, I learned the story of the ambush and fleeing with his young family and all the difficulties and pain the eye injury had caused and continued to cause him. But I never knew Patient without a smile on his face; he was the gentlest husband and father and walked around enduring this horrific physical pain without whining about it or even mentioning it for six months. The day of his surgery, I realized that Patient didn’t really understand how unlikely it was that any of the things one the waivers he signed (saying all the possible complications that could result, including death) might actually happen. Just as he was being rolled back to surgery he asked if he could take just a moment and pray! It was a long and beautiful prayer we had translated. He asked for blessings on all the doctors and nurses in the hospital, and he thanked everyone there and prayed for me and his family, and that God’s will be done with his life–as in, if he didn’t make it through the surgery, that I would keep helping his family and that God would take care of them. It was so incredibly moving! There was not a dry eye in pre-op that day at Regional One, I can tell you for sure. I promise it was the dearest prayer I have ever heard in my life! That’s faithfulness and resilience all rolled into one story and that’s one example of hundreds I’ve witnessed with refugees.”

Volunteers are crucial to the work that World Relief does. Bien Fait reflected on how differently things might have turned out without Melissa: “My life was very difficult without Melissa. When my wife was pregnant, she did a lot for us. Each appointment, she came and took my wife to these appointments. I work, so she was by herself here. If she had a problem, who was she going to call? I would call Melissa, she would come quickly and take care of her. Without Melissa, my life would be very difficult in America.”

Bien Fait was so moved by his relationship with Melissa and her family that he decided to name his newborn daughter Melissa, in honor of his first American friend. He told us, “Because of the mercy she showed to my family, I say, ‘I have to give your name to my little baby. When they went to the hospital for the ultrasound, they said she would bear a baby girl. The same day, I said her name would be Melissa. To show to her how much we love her. How much we say thank you for the things she has done for us. Some people in my family, they ask, ‘Why did you call your daughter Melissa? What does it mean?’ I would say, ‘I did this because a woman with this name did many things for me when I was new to America. It was a white woman who did everything for me. She helped me with everything. For keeping this name in my mind, I will name my little baby Melissa.’ They say, ‘Okay.’ Because they need to know the meaning, and where this name came from. It is not a family name. It is a new name.”

Melissa remembers how she felt when Bien Fait told her of his decision. “I could not believe it, and I immediately burst out into tears and said it was just too much! I have to say, it’s the greatest, sweetest honor I’ve ever received in my life. My three daughters are completely jealous and think that I love Baby Melissa the most now. I have to say she is really beautiful and the happiest little baby you’ve ever been around!”

Melissa and Bien Fait’s story is not necessarily typical, but it is a testament to the life-changing possibilities that emerge when people are willing to get out of their comfort zone and love someone who is very different than themselves. We asked Melissa and Bien Fait what they might say to someone who is unsure about refugees in America.

Bief Fait said, “American people have to leave this idea [being fearful of refugees]. Because, if you need to live better in a new country, you have to meet with the people who live in this country. Because those people, they will teach you how they live in their country. If they leave you, you will be everyday afraid of the rules, afraid of the new laws, but we meet with American people, and they need to be our friends. Because they know how to teach people about culture, and rules, and the laws, and when they teach you, you will be able to live without being afraid of anything. They have to come to help the African families, because we need them. We need to be with them. If they leave us, they do wrong. If the people say, ‘We cannot meet with an African family,’ we have to pray for them. Because that is not Christian. When a Christian sees someone who needs help, he has to help, without seeing the color, without seeing where this person is coming from, because the Bible says we have to help each one, without thinking about the race or the color.”

Melissa responded as well, saying, “First and foremost, STAY INFORMED and understand the truth about the refugee crisis in the world, and arm yourself with actual facts to proactively share with others or if you hear or read misinformation! Get on e-mail lists and advocacy texts, and follow refugee agencies on social media to keep up with current events and know what and who to PRAY for. Go to a volunteer training at World Relief Memphis- even if you don’t end up committing to a Good Neighbor team, there are lots of ways to donate money or goods or services that are greatly needed, as well. SHARE STORIES with others about what you know about refugees. It is almost impossible for even the most hardened folks to hate a maimed grandfather that fled his war-torn homeland and works from 3 in the afternoon until 11:00PM because no one else wants that shift and he just wants to feed his family and save enough money for his green card. There is SO much misinformation and misplaced distrust right now towards refugees. The truth and goodness of their stories deserve to be told, too!”

– By Noah Rinehart, Rhodes College, Bonner Scholar Intern

Photos by Emily Frazier Creative and Peeler family