Posts Tagged ‘Quad Cities’

An Ember of Trust: Marc’s Story

As a child, Marc wasn’t old enough to understand the chaos that enveloped the Democratic Republic of Congo. His family moved to Rwanda when he was four to escape the ongoing civil war. But the aftermath of the civil war left the country divided, and when he returned to DRC at age 12, he was exposed to a new kind of hatred that threatened his life.

“Everyone who looked Burundi or Rwandese had to be killed. Our neighbors started hunting us. If they asked you your name and it sounded Burundi or Rwandese, they would just kill you,” Marc recalled.

He was frightened, and the stress of always having to look over his shoulder left him drained. He craved the freedom of a peaceful childhood. “Even though I was a little kid, police and soldiers used to stop and interrogate me as if I was a man, which I could not understand. I wanted that to stop,” he said.

The dangerous environment drove Marc’s family to relocate to Burundi, where they were placed into a refugee camp. His parents and seven siblings lived in a small house made of mud with just two rooms. Only his sisters could sleep indoors, so Marc and his brothers found places to sleep outside. Despite the “bad conditions,” however, Marc felt more protected than he had ever felt before. He could play with other children without being bullied and they had enough food to eat.

Burundi conditions began to worsen in 2015. Each night became filled with the echoes of gunshots. Just before the turmoil could reach their camp, Marc and his family were selected to relocate to the U.S. It was a miracle.

Still, Marc was uncomfortable. Americans would often ask where he was from because of his accent. Having previously lived in a country that discriminated against his tribe, the endless questions made him feel like he had a target on his back. Resettlement services helped ease his discomfort; after helping his family find jobs, taking his brothers and sisters to school, and frequent check-ins, his caseworkers were the first friendly faces Marc had seen in a long time.

Then, without warning, medical disaster struck. Marc was unable to attend college as he had planned. Instead, he spent most of 2017 and early 2018 in and out of hospitals. The medicine prescribed for his eye problems destroyed his immune system and stomach.

“I was feeling a lot of pain in my stomach. I couldn’t breathe or bathe and was in very very bad shape. I was hospitalized in Chicago; more medicine and surgeries,” Marc said. He had to completely readjust after his long recovery period and was reluctant to start college.

His caseworker, Jen Wood,* met Marc’s struggles with compassion and encouragement. She slowly guided him back to his path with kind words that gave him hope. She told him he could do it, and he started to believe it.

Stillness is a learning process, but the kind staff that helped Marc understand American culture and uplifted him in his time of need reignited an ember of trust he had long forgotten. He’s working on his Liberal Arts degree at Blackhawk college and no longer sees the conflict of his past reflected in his future.

“Right now, I’m feeling good, because I can say that I’m safe,” Marc ended.

He sees a tranquil future abundant with opportunity – and all it took was the empathy of a few others to show him the strength in his heart.

Written by Erica Parrigin

In the Quad Cities, Eagles Give Back

Eamon Garton of Scout Troop 20 is working to achieve the highest rank in scouts: the Eagle Scout. While the title itself is an honor, his goal is to embody its meaning and the obligations it carries.

Eagle Rank “testifies that a Scout has an understanding of his community and his nation, and a willingness to become involved.” Earned by less than 2% of young men in scouting, it’s a pledge to fulfill obligations of Honor, Loyalty, Courage, Responsibility, and Service.

Becoming an Eagle Scout means a mission to give back to the community. To demonstrate his motivation, Eamon has taken on a project to help refugees and immigrants in the Quad Cities. When he learned that proper storage for donations and fresh food given to refugee and immigrant families is a huge priority, he made plans to install hand-built shelving and a large refrigeration unit.

The first step was fundraising. Eamon “sent letters to [his] family, friends, troop, and neighbors,” created a GoFundMe, and reached out to local hardware stores about unsellable lumber. In just a few weeks, he raised $2500.

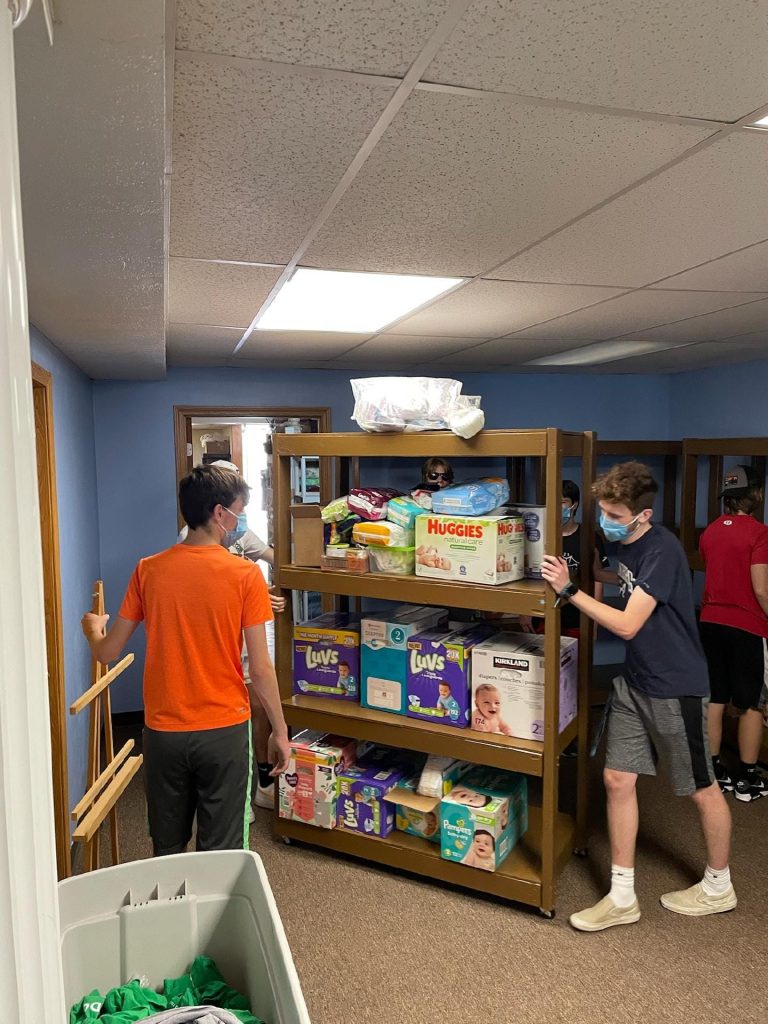

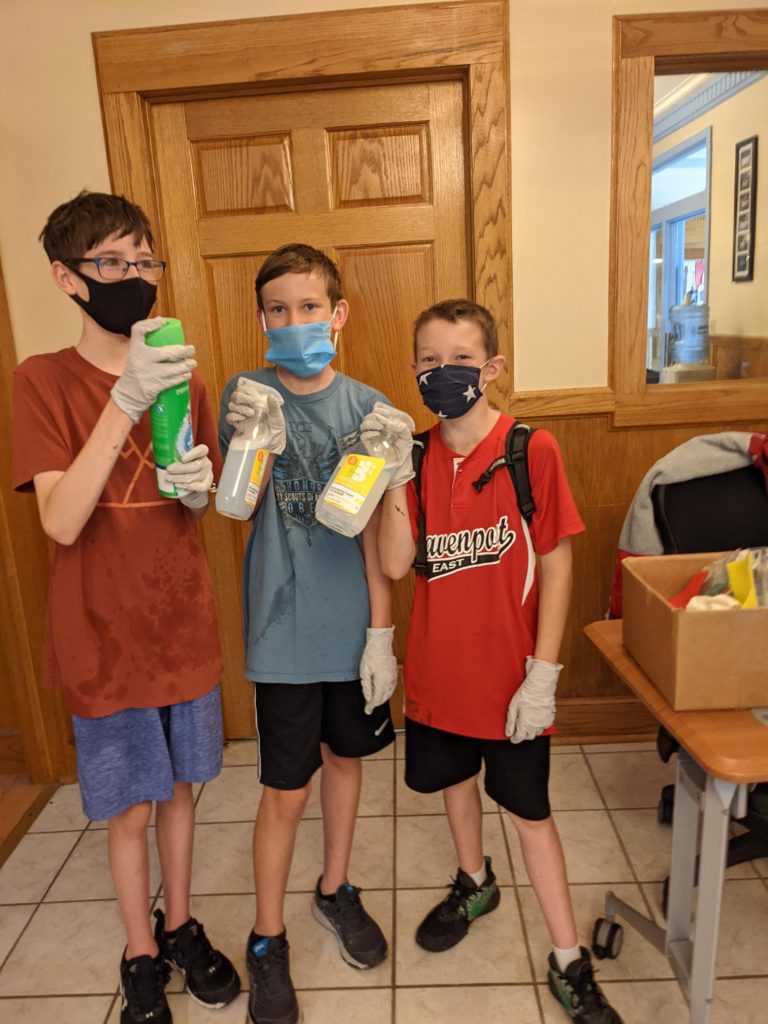

Then, on Saturday, July 17th, Eamon and his troop took over our office to paint and install five rolling shelving units they had built by hand. And they didn’t stop there – they spent the rest of the day cleaning our office and organizing donations. Now, we have the space to accommodate extra items for families with specific needs.

Eamon, you have the qualities of an Eagle Scout and more. From our staff, volunteers, and families: thank you Eamon and Scout Troop 20!

Eamon is still seeking a refrigeration unit to finish his project and his GoFundMe is open for donations.

Photo Gallery

Written by Erica Parrigin

Citizenship Classes are Rooted in Community

“I would say for myself personally, I would not have passed this interview prior to studying or teaching this class,” Habie Timbo said, speaking to the challenges her students face in the process to become U.S. citizens.

While most of her time at World Relief Quad Cities is dedicated to her role as a caseworker for the Immigrant Family Resource program, the remainder is spent instructing citizenship classes. Some agencies that work with immigrants and refugees in Illinois do so through organizations like ICIRR (Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights) and are required to host citizenship classes through the New Americans Initiative, or NAI. But for Habie Timbo, teaching citizenship classes goes beyond just fulfilling a requirement – it’s one of her “favorite parts about [her] job.”

Timbo has been teaching citizenship classes since she started at World Relief in 2019, receiving training from the USCIS and a Chicago-based Adult Learning Resource Center. The intricacies of the process were startling at first.

“Citizenship isn’t just a written test, there is a verbal interview to pass . . . students are required to study 100 Civics questions from U.S. history, as well as demonstrate their ability to read, write, and have conversations in English,” she said.

Timbo is no stranger to paperwork and lengthy applications, but the “very long” N-400 application students submit prior to the interview is the “most difficult document she has ever encountered in her life.” Had she not received the appropriate training, Timbo said she would have struggled to complete the N-400 by herself, even with her undergrad in International Studies.

A sense of respect for those ready to take on the challenge is at the root of her determination to help students feel as prepared as possible. In her 7-week citizenship courses, she helps students build the study skills, English skills, and communication skills that are crucial not just to the interview, but to the rest of their lives.

Timbo’s classroom is filled with people from all walks of life. Individual education levels vary across different age groups and cultural backgrounds, and many of the students are parents with children, full-time jobs, or equally important obligations. Each student has their own unique obstacles; sometimes, a little extra empathy is required.

“You have to be very mindful with the places that people are at and be really flexible with your expectations at times. . . sometimes when you see less dedication than you want, it can be difficult, but [it’s important] to just have flexibility and grace,” Timbo said.

Prior to taking the course, one of Timbo’s students had to return to her country of origin due to a death in the family. Her time spent outside of the U.S. resulted in the rejection of her application and interview despite having passed each section – a cautionary tale about understanding immigration laws which led to an unbreakable bond.

“It worked out, but that student worked so hard in my class. I was so proud of her. . . I got to learn so much about her story and her experiences that it’s really impacted me. I built a lifelong friend with a refugee where it’s like, we’re worlds apart, but we’re in the same place, so it’s really awesome,” she continued.

Timbo’s aspiration to put herself in others’ shoes no matter where they’re coming from is a source of hope, encouragement, and positive energy for struggling students. The opportunity to see her them grow and overcome their barriers is its own reward, and the extra effort is something that stays with them as they progress in life.

“The most rewarding part is when students come back later and tell you, ‘I have my citizenship, we’re citizens,’” she said.

Individuals attempting to gain citizenship take on the challenge because they want to feel valued by their community. In helping students realize that everyone is a “lifelong learner,” Timbo also helps them feel less alienated and gain the confidence to “solidify their place in society” once they complete the course.

And the ultimate outcome of those weeks of studying – citizenship – couldn’t be more important. Becoming a citizen grants the right to vote and actively participate in civic engagement.

“It’s really important that we have immigrant populations that are voting for candidates, that are voting on bills, that are voting for the rights of Americans, because we want their voices to be heard, and we don’t want [these] groups to be kind of a silent minority in our community,” she continued.

And those who become citizens often expand their impact by finding other ways to give back. In the past, Timbo’s students have volunteered to teach citizenship classes, and many of them have chosen to continue their educations so they can become guides for future generations of New Americans. It’s a chain of accomplishment and multiplicity.

“This process is not easy. As Americans, we are very privileged to not know what it’s like to have to justify everything about who you are and speak to everything you’ve done. . . it’s hard work, and we definitely should commend and raise up these individuals,” she concluded.

Written by Erica Parrigin

Grateful to Be a Citizen

Paw Shee loves to read, especially books that teach her about “what happened in the past.” And on her journey to becoming a citizen, citizenship classes became a platform that fueled that desire to learn.

“I love to read the books they gave me about U.S. history,” Paw said, emphasizing, “they gave me whole books!”

Paw recently completed two citizenship courses with two different instructors. Both commended her hard work and her ability to read in English.

“She could read English very well, she always had her homework done,” recalled Susan Llewellyn, Paw’s instructor during her second round of classes, “she always read everything for each assignment.” Sometimes, Paw would be chapters ahead of the assigned reading.

Despite her love for reading and compliments from both of her teachers, however, she expressed concern about her English skills. She wants to be “treated like a citizen,” viewed by others without judgement or fear. For Paw, citizenship means a different way to be seen.

“I wanted to be seen like I am a citizen when I go somewhere. If they question, ‘are you a citizen?’ I want to answer yes,” Paw said.

Llewellyn believes that understanding refugees’ personal circumstances helps to eliminate fear. She always asks her students to share their stories, because “what you hear on the news may be different than what you hear from a refugee.” Paw chose to share her own story in Llewellyn’s class.

She and her family sought refuge in the U.S. in 2014, shortly after faith-based persecution and violence began to escalate in their country of origin, Myanmar. They journeyed outside of the refugee camp they had been living in for the freedom to “go anywhere and practice whatever [they] want.”

Her resettlement was life-changing, and the diligence it took to make the journey followed Paw through her classes. She remained dedicated to learning even as a mother of three during last year’s shift to remote technology.

“She’s a mom, and she was a really good student. . . her kids would be there with her during classes,” Llewellyn said, “she took it seriously and was always prepared.” Paw adapted to remote class technology and completed round two of her classes with ease. Her work ethic, coupled with an innate need to learn about the world around her, drove her straight to her goal.

“I passed the citizenship test,” she said, “My oath ceremony is on July 14th.”

The oath ceremony is the final step in the citizenship process, where participants swear their allegiance and receive their naturalization certificates. It’s symbolic in its representation of hard work, reward, and the obstacles they’ve overcome in their path to citizenship.

After the ceremony, Paw plans to go back to school when she has the time. Her goals are to work on her English skills through ESL classes and complete a highschool education. She’s kept in touch with both of her instructors, to whom she has repeatedly expressed a deep gratitude.

“She’s written to me several times since. She texted me and said she passed the test, got them all right, and thanked me for helping her. She let me know she was grateful,” Llewellyn said.

Paw Shee took a risk in choosing to better herself in the face of fear. And just as she built her future through an innate desire to learn about the past, her own story will serve to inspire those who follow in her footsteps.

“I am feeling so blessed and thankful that the American government welcomes our refugees and lets people come and live here in America. Finally, I am so proud to be an American Citizen,” she said.

Written by Erica Parrigin

Safety at Last: Francois’ Story

Living in Burundi during the Civil War, Francois spent much of his life in fear. He was constantly immersed in the struggle of “two ethnicities fighting against each other.” In December of 1996, he was relocated to a Tanzanian refugee camp with little access to water or electricity. In the context of all he had experienced, safety seemed impossible. He felt frustrated and hopeless as the years passed.

“I don’t remember anything good,” he said. “It was all bad.”

Francois spent ten years in the camp, and it wasn’t until 2006 that he was given an opportunity to resettle. He was welcomed by another agency in San Diego, California. Though grateful to finally be in the US, he began to feel overwhelmed. Everything was newer. He was able to communicate with others through limited English, but he didn’t know how to get around and found it difficult to meet his new hygiene standards. He wasn’t sure how to interact with the culture.

Laughing, he recalled, “I had this idea that I was going to get money from any person I met.”

Even after going to school and becoming fluent in the language, Francois was missing another key element of a stable life in his new country. He didn’t have his citizenship. As his path toward security landed him in the Quad Cities, he found World Relief. WRQC provided the outside support that allowed him to express his concerns without fear. Eventually, with the help of WRQC, he was able to obtain his citizenship. And that’s not all.

“My wife got citizenship through World Relief. My kid got citizenship through World Relief,” he added.

Becoming a US citizen was the last major step in Francois’ journey, allowing him to become fully self-sufficient. He began to focus on the things he enjoys without worry. Because he has always “enjoyed working with people of different cultures,” he grew interested in helping other refugees. He saw a chance to help others overcome situations like his when WRQC contacted him and asked him to be an interpreter.

Today, he’s restoring faith and creating lasting change for the immigrants and refugees that visit WRQC by helping to ease the language barrier. He hopes to spread the peace he now feels after years of uncertainty. The Quad Cities has become his home, and he finally feels “safe.”

Written by Erica Parrigin

More to Offer: Abe’s Story

In honor of the recently increased refugee cap, we’re sharing stories from some of the brave Quad Cities refugees and immigrants who strive to create a community of welcome for those following in their footsteps. Together, we can [Re]Build.

Mbanzamihigo “Abe” Ibrahim’s first memory of the U.S. is of fireworks. “It was two days away from the Fourth of July. I had never seen, experienced, or even heard of fireworks,” he recalls. On that day, he was blessed with a sense of hope that would last a lifetime.

Abe’s family was granted asylum in the U.S. when he was just ten years old. He had always dreamed of a way to make his mark on the world. But having been “basically born” in a Tanzanian refugee camp, he was never asked what he wanted to do when he grew up. His family was focused on survival.

“I would be done with high school, but probably wouldn’t be doing anything with my life,” he said.

When his family’s case finally made it off the waiting list, Abe was scared. The music, the food, the language – all of that was about to change.

With a little encouragement, Abe’s fear turned into passion. Sometimes, the question “What do you want to do with your life?” is just as important as a safe and accepting environment.

After World Relief Quad Cities helped Abe’s family settle into their new home, he re-enrolled in school. Abe was finally around people who asked him about his future – the support he never realized he needed. “Like a sponge” absorbing information, he learned English in just one year.

Abe reflected the kindness he was shown and quickly began to make new friends.

“When you’re surrounded by good people, you become a good person,” Abe continued.

Most importantly, he didn’t lose touch with his culture. Though he was born in Tanzania, Abe embodies his parents’ Burundian values.

One of those values is community. By showing compassion to others, especially when they’re vulnerable, together we can build loving communities whose actions reach the hearts of everyone involved.

Abe’s main goal in life is to give young people the same support that he received when he was a child. As someone who “looks and talks like them,” he hopes to be a role model they can truly relate to.

While he pursues his psychology degree at St. Ambrose University, he works as a Preferred Community Caseworker at World Relief Quad Cities. Abe regularly shares his story at his organization’s events and is often recognized for his speaking roles at their March 2021 Gala and recent partnership with the Putnam Museum, The Colors of Culture exhibit.

He also holds a platform that advocates for the success of Burundi children, hoping to visit one day and tell them how much they have to offer.

“I want to show them how big the world is,” he said.

From fear and uncertainty to inspiring and educating others, Abe has remained kind and courageous – he will always find more to offer.

Written by Erica Parrigin

Surviving to Thriving: Dim’s Story

In honor of the recently increased refugee cap, we’re sharing stories from some of the brave Quad Cities refugees and immigrants who strive to create a community of welcome for those following in their footsteps. Together, we can [Re]Build.

When Dim was a child, her father had to leave Myanmar to work in another country. It was the only way for her family to obtain a survivable income. Today, minimum wage in Myanmar is 4,800 kyat, or $3.00 US. It was even less when Dim was growing up. She felt discouraged as she watched her loved ones labor away in exhausting rural jobs that left them unable to afford necessities like food and medical care.

“In Myanmar, it’s hard there. Even if you work hard you don’t get paid a lot. We didn’t see a lot of other people because we lived in a small town. We had narrow-minded people. There was nobody to dream,” she said.

But Dim has always been a dreamer. She imagined a future where she could take care of her family and friends.

Her parents thought about her education while they worked. Determined to help their daughter achieve her dreams, they moved to Malaysia and enrolled her in school for the first time.

When Dim entered high school, however, her opportunities were interrupted. She couldn’t continue her schooling unless they moved again. The family knew the transition wouldn’t be easy, but they refused to accept the “this is how it will always be” mindset that was so common in their previous home.

In 2016, they decided to permanently resettle in the US. Dim was amazed to see the welcoming crowd at the airport and knew everything was about to change.

“World Relief Quad Cities made sure we had food and furniture. When we got here, everything was already in our house. They helped us to go to the doctor, taught us how to use everything, how to go somewhere, and they even taught my mom how to take a bath,” she recalled. She quickly understood English with the help of a caseworker who visited her house and began to excel in her high school classes.

The college education that had been just out of Dim’s reach suddenly became a reality when she was accepted to Augustana. She plans to major in chemistry and hopes to become a dentist. For Dim, dentistry illustrates what it means to “love thy neighbor.” Her neighbors in Myanmar never knew dental care existed.

“We didn’t know what dentistry was, but when I came here, World Relief Quad Cities helped me get dental care. If I become a dentist, I’m going to help people back in my country.”

With her brightness and enthusiasm finally given room to grow, Dim has embodied a mission to rebuild the lives of the vulnerable. She can’t wait to inspire joy and confidence by bringing new smiles to small communities like the Myanmar town she once felt restricted by.

Ultimately, she wants to show others that there’s more to life than survival.

“I still have a lot to learn, but everything is better now,” she added. With the days of draining physical labor behind them and goals to look forward to, Dim and her family are no longer just surviving – they’re thriving.

Written by Erica Parrigin

My Time as a Remote Intern

Throughout four months of balancing remote work, a pandemic, periods of quarantine and college, I’m now at the end of my internship with World Relief Quad Cities.

During the past semester, I worked as a communications intern. Most of my projects were communication-based and included things like writing articles and creating social media posts. I also helped with some video editing, data entry, volunteering, and design work.

Completing an internship during a pandemic is a unique experience. For one, it was largely remote, although I was able to come into the office more towards the end of the internship.

That meant that I had limited contact with the staff and, sadly, never met a client that we serve. The closest I got to getting to know clients was talking with them on the phone for a couple of minutes. Despite having limited contact physically, I still felt like I was part of the team and making a difference in the organization for the people we help. Through emails, texts, phone calls and meetings, I was able to connect with the staff and get an idea of what it’s like to work at World Relief Quad Cities.

Without a doubt, the highlight of my internship was anytime I was able to go into the office. The work environment was always so positive and I loved getting to know and work with the staff in-person.

Right at the start of my internship, the diversity of the staff at World Relief was something I noticed and valued, and it was something I’d never experienced in a workplace before. There’s such a wide variety of people from different places with different backgrounds, and everyone brings something different to the team.

All of the staff members want to help immigrants and refugees in any way they can, and they do exactly that everyday. I saw how they all use their unique skills and backgrounds to contribute to that goal. They also often put in extra time and effort to help, often at no benefit of their own. That kind of generosity and desire to help others was amazing to work with and inspired me to do the same.

My time at World Relief Quad Cities helped me understand the kind of work they do and get a first look at the work environment. Before I interned here, nonprofit work was not something I had thought about pursuing. Now, I’m extremely thankful for the opportunity to intern at World Relief because it opened up the possibility of nonprofit work and new opportunities I could see myself pursuing after graduating college.

World Relief does so much good for the community and has such a big impact on the immigrants and refugees they help. By being an intern there, I also was able to utilize my skills and background to make a difference. The kind of work they do is really important, and my time at World Relief showed me how much I have to offer and how I can use my skills to give back to the community in a really meaningful way.

Written by Olivia Doak

A Mother’s Guidance Makes an Impact

Because of her mother, Anna Triska knew what she wanted to do with her life from the time she was in second grade. Triska’s mother is a preschool teacher, and ever since she was little she would help her mom with projects and setting up her classroom. From then on, she knew she wanted to be a teacher like her mom.

“I knew exactly what I wanted to be since second grade…and I have always known that because of her,” Triska said.

Triska is a junior at Augustana College and is in a class called Human Geography of Global Issues. In the class, students learn about human migration and issues people face when immigrating to a new country.

To apply that knowledge, Triska is in a small group with other classmates that meets with a World Relief family via google meets once a week. The family she meets with has been in the United States for about five years and has six kids ages 5-16. Triska said she loves getting to sit down with the kids in the family and play games, have fun and relax.

For the most part, Triska and her group work with the nine-year-old child, and she said it’s the highlight of her week. But more than it just being a fun experience, Triska said she’s gained some new insights about what it means to be a refugee.

“I think working with them has helped us apply that knowledge of what it means to immigrate from one country to another,” Triska said.

Triska also said it’s helped her gain valuable insight that will help her as a future teacher.

“As a future elementary school teacher, [this experience] helps me understand families that may have immigrated from a different country, where they are coming from and what their home would be like,” Triska said. “I think that helps me be more aware of my future students and what their home life would be like.”

For the most part, the children in the family speak English well, but the mother does not. Even so, the mother still helps the kids set up the call and sits with them throughout the duration of it.

“[She] just feels like this warm presence for the kids to just feel more comfortable to sit with us,” Triska said. “Because we are strangers and we are a lot older than they are, it can be intimidating, so it’s kind of nice to have her there just to reassure them that they are okay and that they are safe.”

Triska also said she’s told her own mother about her experience meeting with the World Relief family. Triska said her mom was excited that she had the opportunity to do something like this and that it’s something not a lot of classes would offer their students.

“She just kept saying, ‘that’s so cool, that’s so awesome,’” Triska said. “She just loves that we’re getting that experience and thinks it’s extremely beneficial for me as a future educator.”

Triska said that her mom is her best friend and biggest supporter, and that her mom has had an incredible impact on Triska’s life and who she is as a person.

“She has shown me what it truly means to care for another human being,” Triska said. “That has translated into me being such a people person and being a good support system for my friends and my other family members.

Written by Olivia Doak

Appreciating Those Who Sacrifice it All

Being a mother is a big job, let alone being a mother of four kids in a new country where you don’t speak the language.

But for many families and mothers of families that World Relief serves, this is a reality.

Students from Augustana College have been spending time with client families via google meets as part of their Human Geography of Global Issues class. First-year Giovanni Martinelli said he’s seen first-hand the kind of care and compassion the mother of their family shows daily, even with the language barrier and the mother knowing limited English.

“Without any direct conversation with her, she seems very caring to her children and she tries to help them interact with us,” Martinelli said. “She primarily focuses on the little ones. There’s a small child that’s maybe around one year old, so you can tell that she definitely takes care of them and tries to put them first in everything that she does.”

Senior Rachael Lockmiller meets with a family with four kids all under the age of 10. Her and her classmates usually help with homework or play pictionary and other games with the kids during their google meet call.

Lockmiller said that within the one hour a week they meet with the family, she’s noticed how the mother is constantly in-tune with her children.

“You can just tell that she’s a strong, independent woman, and I hold a lot of respect for her,” Lockmiller said. “Even just in the hour that we’re talking to them, you can see her running around in the background holding the baby, trying to make food, going to the bathroom, changing the baby and making sure the other kids are behaving themselves.”

Martinelli said that the experience meeting with the families has been eye-opening. Even with the language barrier and limited communication, the opportunity to learn about a new culture and meet with new people has been valuable.

“Just talking about the challenges I’m facing, I can’t even imagine what they’re going through,” Lockmiller said. “Just even going to the grocery store, not being able to read English or speak English..and we just take that for granted and don’t even realize how blessed we are.”

Most of all, Lockmiller and Martinelli recognize the strength and caring of the mothers of the families. Lockmiller said she appreciates how much bravery it takes to move to a new country to seek a better life for your family when you don’t even speak the language.

“Whatever it was that they had to do to get over here… I can’t even imagine how much strength she has to have,” Lockmiller said.

Written by Olivia Doak